Are We Getting Smarter?

Rising IQ in the Twenty-First Centuryby James R Flynn

Analogy of the decathlon events. Overall decathlon score should indicate quality of an athlete across at least half the skills - a good 100m runner should also be a good hurdler and high jumper. But there has been social change over last 50 years - people are obsessed with 100m ("fastest man on the planet") so athletes find it financially and sexually worthwhile to concentrate on that event, so the performance of the 100m runners increases far more than other events.

We have taught new ways of thinking. Now abstract thinking valued, whereas in the past only concrete ideas - people needed to solve things just in the real world. So, tell a concrete thinker "There are no camels in Germany. Berlin is a city in Germany. Are there any camels in Berlin?" He says "I don't know. I've never seen a German city, but all the cities I know of have camels in them, so Berlin probably has camels."

100 years ago tests asked for concrete knowledge - "What is the capital of ...?" and they saw very few abstract images - photos, playing cards, musical scores. Today we are bombarded with symbols.

IQ gains are scattered - big gains in abstract thinking areas but little change in arithmetic scores. Suggest that it is because maths is not purely logical skill - it is more like exploring a separate reality with its own laws which are different to the laws of the natural world.

The TV shows of the 50's and 60's were simplistic, requiring virtually no concentration to follow. Beginning with the 1981 Hill St Blues, single episode dramas began to be replaced by dramas that had as many as ten separate threads in their plot lines. An episode of 24 connected the lives of 21 characters, each with a distinct story.

Sum up with: we live in a time which poses a wider range of cognitive problems than our ancestors encountered, and we have developed new cognitive skills and the kinds of brains that can deal with theses problems.

More books on Mind

(LT Review)

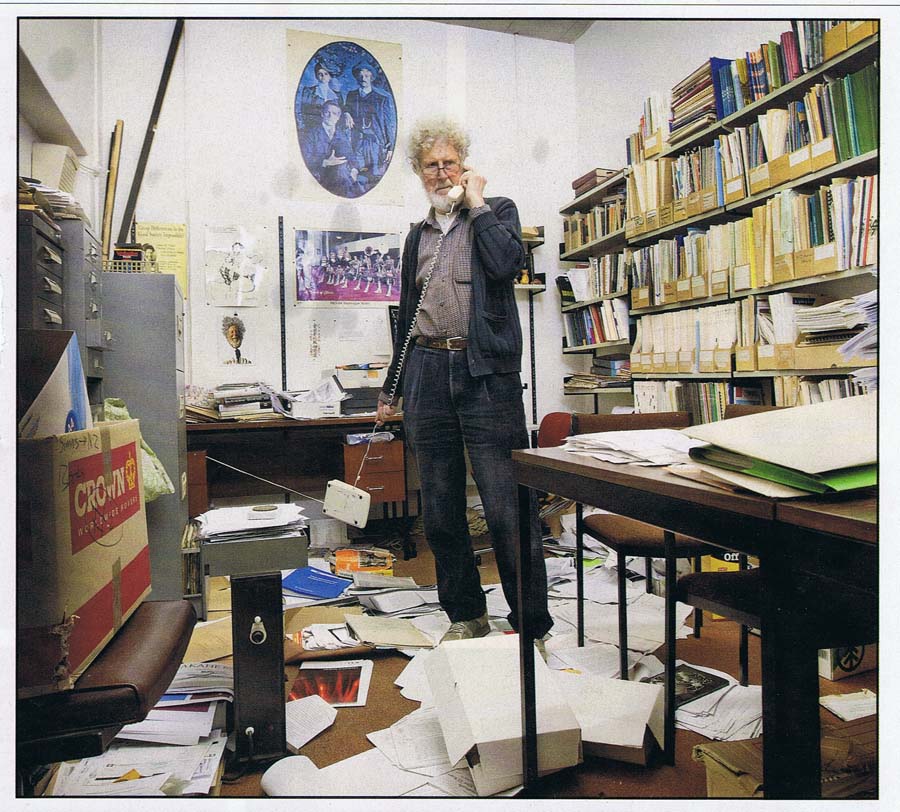

Now aged 78, James R Flynn can confidently look forward to immortality. His name will forever be attached to one of the most contentious, baffling and, for me, exhilarating scientific discoveries of our age. The Flynn Effect is the name given to the discovery that, across the world in the 20th century, human intelligence seemed to be increasing at a phenomenal rate. Flynn, a New Zealander, demonstrated this by giving old IQ tests - say, from the 1930s - to contemporary students. Their results were spectacularly better than the original test-takers', suggesting that our species was undergoing an enormous leap in intellectual capacity.

For this to happen, evolution would have had to have accelerated to light speed. Responses to the discovery varied from there must be something wrong with IQ tests to there must be something wrong with Flynn. Well, Flynn seems okay to me. The point about IQ tests is that they were thought to be a culturally neutral, universally applicable way of measuring human intelligence, a quality known to the statisticians as 'g'. In theory, a test taken by a Masai warrior would produce comparable results to one taken by a New York stockbroker. This is, as I have been pointing out for years, superstition.

So what was happening? This book is Flynn's answer and I think I can safely say it is one of the most extraordinary science books I have ever read. It is not for the faint-hearted. Unless you are a statistician, large parts of it will be almost impossible to follow. In spite of all that, Flynn himself emerges as a tough-minded, somewhat crusty but very humane character. I have seldom finished a book wanting to meet the author, but I want to meet Flynn.

In a very small nutshell, his explanation for the Flynn Effect is this. Human potential at birth is unchanged; we are not, in any fundamental sense, becoming a smarter species. But the way we live has changed. IQ tests were first established in the 19th century at a time when daily life was concrete and practical. The tests, however, had to be abstract to make them culturally neutral. People, therefore, found them harder because they were unaccustomed to such modes of thought.

In the 20th century, greater educational possibilities combined with technological advances introduced abstract thought into daily life. It takes, for example, a high degree of abstract thinking to operate a mobile phone or computer. People became better at IQ tests and, steadily, the scores rose. So IQ scores are meaningless unless their date and social norms are taken into account. This leads to Flynn's grandest and most fervently held view - that a lack of social awareness leads inexorably to folly. Indeed, the penultimate chapter is a list of 14 examples in which science has failed because of social blindness. Low-IQ people, for example, are not more prone to violence and, contrary to widespread assumptions, no clear link between nutrition and IQ has been found.

The abstract, scientific imagination can simply seem foolish when confronted with more concrete ways of thought. Flynn includes one hilarious conversation between a western researcher and some isolated rural people in Russia to demonstrate the abyss that lies between the concrete and the abstract. The researcher tells them there are no camels in Germany so how many camels do they think there are in B, a specific German city? "I don't know," is the answer. "I have never seen German villages. If B is a large city, there should be camels there." These people aren't any less intelligent than the researcher - their minds just work differently. They focus on the practicalities they know rather than hypothetical possibilities.

The implications of this explanation are startling. In the US, for example, the death penalty tends to be forbidden for culprits shown to have an IQ of 70 or less. The assumption here is that IQ is like a social security number: it stays with you through life, always saying the same thing. But - and Flynn seems to have spent a good deal of time testifying in American courts to this effect - everything depends on when the accused was tested.

The point here is that IQ is defined as mental age over actual age multiplied by 100, so the average should always be 100. Over time the tests are recalibrated and, as people seem to get better at them, they necessarily get harder. The number is in a constant state of flux. As Flynn puts it, IQ is not a number; it is a message. The resulting variations will be matters of life and death. The legal system remains baffled as to how to deal with this.

The misuses and misunderstandings of IQ tests can be very dangerous, and not only in the limited realm of judicial executions. They are neither culturally nor temporally neutral, so no simple figure should be taken on trust - but that is exactly what racist interpreters of the figures have done. Flynn's interpretation overturns one of the most dangerous myths of IQ research - that blacks have been shown to be fundamentally less intelligent than whites. With what seems to me to be a series of cast-iron statistical analyses, he shows that this has, in fact, never been proved and that the logic on which it is based - 'this steel chain of ideas' - is flawed. What the evidence actually shows is that racial differences, once all external factors are removed (primarily the social and cultural context of the testees), seem to be almost undetectably small.

The same seems to be true of gender differences. Flynn savages the research involving university students over several decades in Britain and America as being hopelessly - though not deliberately - biased against women in its sampling. Current signs of women's IQ rising should be similarly explained if they can be seen as a correction based on improved sampling.

The developing world, which still registers very much lower IQs than the developed world, need not worry. Flynn points out the mean IQ in America in 1917 was 72; it is currently just under 100. His effect is fast-acting.

But, as he repeatedly insists, this research is in its infancy. There is much more work to be done and much of what has been done in the past has been distorted by delusions and preconceptions, also by various forms of censorship. "When you suppress an idea," booms Flynn in the book-s last paragraph, "you suppress every debate it may inspire for all time."

In the end, once - if - you get through the stats and the astounding leaps of Flynn's mind, Are We Getting Smarter? is an optimistic book. It demonstrates that the human mind is capable of adapting quickly and painlessly to the ever more complex world it has created. The answer to the title's question is: yes, we are indeed getting smarter, in the sense that we are keeping pace with our inventions. We are not improving on our biological destiny; rather we are making a world that is more like an IQ test. The next question - can we keep it up? - is the big one.

Books by Title

Books by Author

Books by Topic