No One Understands You and What to Do About It

Heidi Grant Halvorson

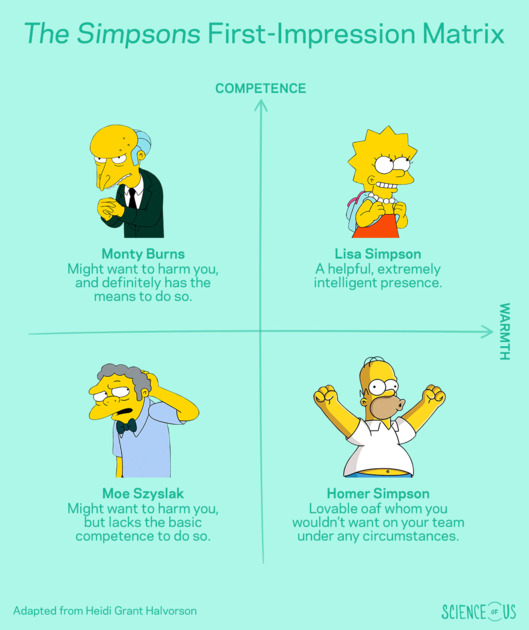

The Simpson's Matrix

There's a reason why first impressions are a source of so much anxiety: It's simply impossible to know how someone meeting you for the first time is going to respond to you, and whether they're going to accurately or positively gauge who you are as a person. And as Heidi Grant Halvorson, a Columbia researcher and author of No One Understands You and What to Do About It, told Science of Us last month, these concerns are valid: Once first impressions set in, they can be very hard to change.

What most people don't realize is that as tricky as cultivating a positive first impression can seem, it mostly comes down to just two things. According to Halvorson, 'We're wired to figure out very quickly' how warm someone is - that is, whether they appear to be a friend or foe - and how competent they are - how likely they are to be able to carry out their intentions toward us.

And the impact of these simple judgements can be huge, Halvorson said: 'Something in the 80 to 90 percent range of how positive a first impression is of another person can be explained by those two dimensions alone.' The good news is that while this knowledge won't guarantee that you ace your first impressions, it does at least reveal the grading rubric: If you know that warmth and competence matter more than just about anything else, you can plan accordingly.

When she's giving talks about the science of first impressions, Halvorson likes to rely on a simple two-by-two matrix of Simpsons characters she came up with. 'I think you can explain every psychological principle with The Simpsons,' she joked.

Here it is, with text added by Science of Us.

There's an instinctive side to first-impression judgements about warmth and competence, Halvorson said - they're 'basic animal behavior.' Which means, unfortunately, that it's possible to give off certain signals about your warmth and competence without even knowing it: Since these judgements are largely automatic, even if the person you're meeting for the first time meeting has never read a word of this sort of research, in all likelihood, you will be slotted into one of these categories, and fairly quickly, too.

The best-case scenario, of course, is to find yourself in the upper-right quadrant. 'If you're high in warmth and you're high in competence, you're like Lisa Simpson,' said Halvorson. 'Lisa's the one you want to be: She's smart and she's good, and you feel like she would be a really good friend and you trust her.'

If you half-ass the warmth part, though, and focus only on cultivating an air of competence, you may end up coming off as a Mr. Burns. Halvorson said this is a common mistake when people are nervous. 'What people tend to do is really try to show how competent they are - they try to talk about their skills and abilities and what makes them awesome - and they neglect to send warmth signals,' she said. In the absence of these signals, 'you end up appearing cold. And cold and competent is Mr. Burns.' Halvorson stressed that if you don't give off some rather explicitly warm signals, the person you're meeting's default response won't be to see you as 'neutral,' but rather as cold - Burns territory.

The flip side of this error is to focus on seeming like a really good, warm guy or gal, but without also broadcasting some indications that you're competent. If this happens, you'll end up in the Homer quadrant - maybe a fun person to get a beer with, but certainly not someone whom people would want on their team in a high-stakes scenario. 'We tend to feel pity or compassion' toward these sorts of people, Halvorson said - emotions you are probably not hoping to elicit.

Finally, if you really flunk your first impression, you could find yourself in the dreaded Moe quadrant - neither warm nor competent. This 'elicits disgust and aversion you just don't want to be near that person,' said Halvorson. The Moes of the world are too pathetic to even be feared.

Halvorson said that people have a lot of trouble with how to project warmth. This is understandable: Whereas first-impression evaluations of your competence, in theory, at least, center on tangible stuff like your level of knowledge and prior qualifications, warmth is a bit more amorphous of a concept, and not everyone is naturally good at emanating it.

'Warmth isn't about being touchy-feely and huggy,' explained Halvorson. Rather, she said, it's mostly about simple-sounding stuff that people simply forget in the moment: 'expressing interest in another person, expressing empathy when that's appropriate,' to take a couple of examples. Body language is also key: It's important to look someone in the eye when they're talking to you, for example, and to 'nod a little bit at the end of their sentences,' without overdoing it. And if someone's smiling at you, make sure to smile back - she said people find it creepy when a smile isn't reciprocated.

In the heat of an important first encounter with someone, it can obviously be easy to lose track of some of this. If you're not sure how you come across to new people, Halvorson said the best bet is to simply ask a trusted friend or co-worker, since we're not very good at evaluating our own performance on complicated social tasks. But if you do end up in the Burns quadrant - or, worse, marooned in Moe's Tavern - don't worry: Halvorson has you covered if you need to undo the damage.

(Science of Us)

Being misunderstood is a weirdly potent and unpleasant experience, and one that's happened to all of us. Nobody likes feeling as though others aren't seeing them for who they are, and in addition to causing hurt feelings, these sorts of misunderstandings can have both personal and professional consequences - your boss thinks you're lazy because you come in late (you were up until 1 a.m. working on that demanding new project); your partner thinks you're callous because you forgot to at least text her to ask how her big presentation went (you were preoccupied all day because of the boss thing).

In her new book from Harvard Business Review Press, No One Understands You and What to Do About It, Heidi Grant Halvorson, a social psychologist and associate director of Columbia Business School's Motivation Science Center, offers a clear, compelling account of both why these misunderstandings occur in the first place, and what can be done about them.

Like so many other errors of human perception, misunderstandings about other human beings are rooted in the many shortcuts the brain has developed to make sense out of an endlessly complex world. Luckily, there are strategies one can employ to help defeat mis-perceptions when they arise.

Halvorson elaborated on these principles in an interview with Science of Us. Here are five key takeaways:

Accept that cliches like 'You only get one chance to make a first impression' exist for a reason, and are depressingly accurate.

Imagine if the first time you met someone, they were crying. What effect would that have on you? We'd all like to think that we're careful in our judgements of other people, that we don't rush, but the fact is that we do. Given what we know about how first impressions are formed, it's much more likely that you would make a quick, knee-jerk judgement about the person crying - maybe that they're naturally weepy or suffering from depression - than that you'd understand maybe they're just having a particularly bad day or had received some bad news.

Part of the reason first impressions are so sticky is that humans are 'cognitive misers,' as psychologists put it. That is, our brains are designed not to waste energy on stuff that probably won't matter. If the only real information you have about someone is that you saw them cry, then there's a decent chance they are a naturally sad or weepy person, and our brains are content to leave it at that. The problems arise when someone's behavior tells us less about who they are than our knee-jerk brains might think.

Halvorson explained that when she's asked what people can do when they feel like they are being misjudged as a result of a false first impression, 'I always want to be able to say to people, 'There's this really easy thing you can do.' But the truth is, the more you know about person-perception, the more you realize how hard it is to change first impressions.' There are some solutions, though. But understanding them requires you to first ...

Understand the power of Phase 1 and Phase 2.

Readers of Daniel Kahneman's wonderful Thinking, Fast and Slow might remember the idea of System 1 and System 2 thinking. Basically, System 1 is for quick, automatic sorts of thought, like determining the value of 1 + 2 or responding when someone asks you your name. System 2 is for more careful, deliberate judgements, like trying to assess a problem's best solution or determining the value of 461 x 17.

Similar principles guide our perceptions of others. Referencing work by Dan Gilbert, Halvorson described Phase 1 as 'this automatic phase, and it always happens, and that's where things like stereotypes come online, even ones you don't believe.' When your first impression of someone ends up being false, either because you misinterpreted something about their actions or fell victim to a stereotype, that's a Phase 1 error.

Phase 2, on the other hand, is a more careful mode of perception. During it, 'We might actually take a look at whatever kind of quick and dirty conclusions we drew about another person,' said Halvorson, 'and then say, 'Okay, well is that right, or are there other explanations [for their behavior]?' It would be an exhausting and unnecessary use of cognitive resources to have Phase 2 active all the time - how vital is it, really, that you develop a truly accurate view of the guy you have a brief interaction with at the corner store? - but nudging people toward Phase 2 thinking can help correct mis-perceptions they have about you. More on that in a bit.

Realize that you are probably a terrible judge of how other people view you.

Humans, Halvorson explains in her book, are consistently poor judges of how other human beings view them. 'We know when someone else is making a good impression, but we don't know when we're not doing it.' In other words, if you think that your (wonderful) qualities will be transparently obvious to every new person you meet, you're almost certainly wrong.

In fact, one of the easiest ways to suffer the consequences of being misunderstood is to assume that the 'real' you consistently shines through to others - especially others with whom you don't spend a lot of quality (Phase 2) time. In these cases, 'People are going to be wrong about you a nontrivial amount of the time,' Halvorson said, 'because people are going to get the gist, but not the details.'

Ask a friend for some brutal honesty.

Halvorson had a straightforward, if slightly fraught, suggestion for how to get around our inability to accurately gauge how others perceive us. 'Take somebody you really know who you trust' - it doesn't matter who, as long as they're spend a lot of time with you and are likely to give honest feedback - and ask them to complete the sentence: 'If I didn't know you better, I would think ... '

People you know well, after all, are the only ones who have a good enough sense of you to understand what others' Phase 1 judgments of you might get wrong - and what they might get right. Sure, having someone complete that sentence might be awkward, but it's probably worth the temporary discomfort to better understand how the world sees you.

When you need to repair a mis-perception about you, chose either the bombardment method or the teamwork method. Once misunderstandings arise, they are, for all the reasons mentioned above, very difficult to dislodge. Halvorson offered two suggestions, though, that she said can effectively help force someone to see you for who you really are.

One approach, best used when you know exactly what mis-perception you're hoping to correct, is to 'bombard the person with attention-getting evidence that they are wrong about you,' Halvorson said. It could take a very long time - Halvorson specifically said that if you bring someone who thinks you're uncaring coffee just once, they will, if anything, think you're simply trying to manipulate them - but there's a war-of-attrition aspect to this. If you provide counter examples over and over and over, you often can rewire someone's view of you. If someone is faced with a towering pile of evidence that runs counter to their initial judgements about you, it will make it 'unavoidable for them to go into Phase 2,' she said. 'It's a dissonance creator - you're creating so much information that is counter to what they believe, that the discomfort of that starts to build” and they are forced to reassess their previous position.

The other approach, which is more general and might take less time, is to 'create a situation where that person who has the wrong idea about you has to work with you in some way,' she said. 'In other words, their outcomes depend on you in some way.' If you can get yourself on the same sports team or project or volunteer organization as the person in question, 'Unconsciously, the perceiver's brain becomes very motivated to get you right. Suddenly there's a real increase in the motivation to be accurate, in the motivation to go into Phase 2 and just make sure that they're really understanding [you] correctly.' That's because 'when we work together, you have to understand one another's behavior,' said Halvorson. So working alongside someone, in other words, makes it more likely you'll get a chance at a 'second impression.'

More books on Persuasion

Books by Title

Books by Author

Books by Topic