Wait

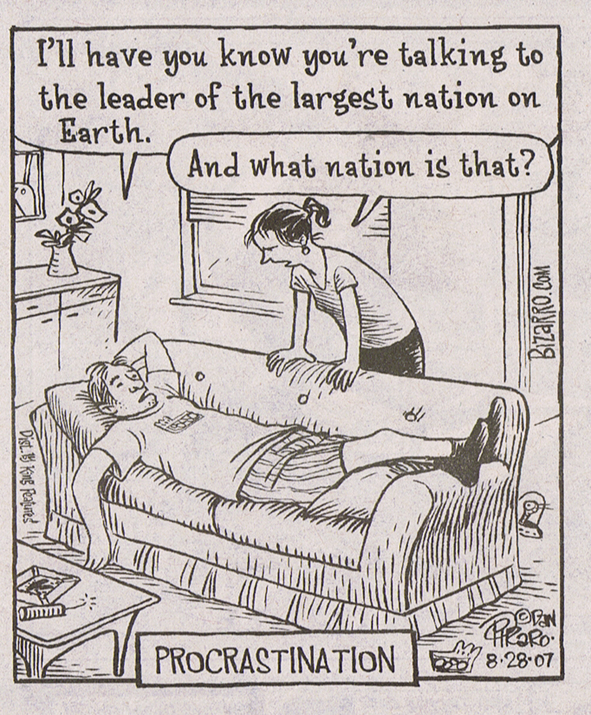

The Useful Art of Procrastinationby Frank Partnov

Procrastination isn't all bad - putting something off might mean that you make a wiser decision or produce better work. Frank Partnoy on why manana is soon enough for everyone.

Do you put off planning that dinner party, even though you want to see your friends? Is your daily to-do list as long as your arm? Might you even be among the millions who think they have a chronic procrastination problem?

If you said yes to any of these questions, you are in good company: from St. Augustine to Leonardo da Vinci to Duke Ellington to Agatha Christie to John Huston to Bill Clinton - all were masters of the arts of putting off until later what they could just as easily do immediately. Like many of my colleagues and friends, I tend to procrastinate and I've always bristled at being told that it was bad. If I have creative breakthroughs it is because I put something off, not because I meet a deadline.

We tend to feel guilty about procrastinating, but is its bad reputation well deserved? Studies find that although procrastination is problematic for some people, others can still get plenty done without stress or low self-esteem. It can be a force for good, helping us to become more productive, not less. In fact, the urge to procrastinate is a fundamental part of the human condition; the ability to do so is a key factor distinguishing us from animals.

I've always had a love-hate relationship with procrastination. On one hand, I seem to be pretty good at it and it often helps me to avoid stuff I'd rather not do. On the other, I often feel terrible about myself when I am putting off tasks. I wrote my book Wait: the Useful Art of Procrastination to explore the role of delay in decision-making in our fast-paced, technology-packed lives.

As someone who studies finance and used to work on Wall Street, I was particularly puzzled by the horrific snap decisions bankers and regulators made during the recent financial crisis. What if senior managers at Lehman Brothers hadn't advocated so strongly gut instincts and quick decisions? What if regulators had taken more time to understand the problems at Lehman and throughout the financial system?

Back in the 1990s, procrastination had served my colleagues in Morgan Stanley's derivatives group well; a few dozen of us made $1 billion in two years while playing chess, reading hunting magazines and not returning phone calls. Today's bankers might be quicker and more efficient - and we didn't always have exemplary behaviour - but at least we didn't bring the financial system to its knees.

I was a precocious procrastinator.

As a child I refused to perform basic chores such as making my bed until there was a compelling reason to do so. My mother saying she didn't want to see the mess didn't qualify as compelling; I told her she could simply shut my bedroom door. And a vague threat that guests might visit didn't qualify either. What if it was a false alarm? Even after my parents announced that relatives were coming over, I insisted on hard evidence - a car in the driveway or a knock at the door - before I would agree to tidy up.

The expertise I developed as a child in what I now call 'delay management' served me well later in life. At college and law school I calculated how much time it would take me to write a paper or study for an exam, counted back that many days before the due date, and didn't start until then. More often than not, it worked.

Nearly two decades ago, Morgan Stanley was the ideal spot for me to hone my procrastination skills. I admired and emulated one of my bosses who never prepared for a meeting until a few minutes beforehand. By delaying my own preparation I created time to take on new projects. I also got good at working under intense, last-minute time pressure.

In academia, where I have been for the past 15 years, procrastination is practically a job requirement. Academics regard deadlines as merely aspirational; law professors who finish work early are viewed with derision. I tend to finish my best research projects and lectures at the last possible moment. I just wish I felt better about it.

A couple of thousand years ago I would have been more at home. In ancient Egypt and Rome procrastination was thought to be useful and wise. Only a handful of early writers, such as Cicero and Thucydides, admonished people not to delay. Indeed, until the mid-18th century procrastination-hating was a minority view. Then the English came along and ruined everything with "a stitch in time saves nine" and "the early bird gets the worm". Americans imported the Earl of Chesterfield's admonition: "No idleness, no laziness, no procrastination: never put off till tomorrow what you can do today." We read Jonathan Edwards's sermon Procrastination, or the Sin and Folly of Depending on Future Time. We built on the Puritan work ethic, which wasn't much fun but became a major part of Anglo-American culture. Over time, Chesterfield and Edwards seeped into everyday life, along with the biblical references that Edwards peppered throughout his homily, especially Proverbs 27:1, which advises, "Boast not thyself of tomorrow; for thou knowest not what a day may bring forth."

Beginning in the 1970s, the do-it-now anti-procrastination industry burst on to the scene. Managers began following Peter Drucker, the self-styled 'social ecologist', who advised, "First things first; second things not at all." Jane Burka and Lenora Yuen wrote Procrastination, a bestseller about how to avoid it, and their procrastination workshops became popular. The self-help guru Stephen Covey told us that highly effective people do "first things first." David Allen coached us in Getting Things Done.

The world became obsessed with productivity and efficiency, and people everywhere came to despise procrastination. Yet even as we began to feel terribly guilty about procrastinating, we did it even more. The percentage of people who say they do so 'often' has increased sixfold since 1978. Students report spending more than a third of their time putting things off. According to some studies, nearly one in five adults is a chronic procrastinator. Today, the world is divided in many ways; but nearly every country is a procrasti-nation.

Our conflicted feelings about procrastination are reflected in modern research. Many psychologists follow a definition from Piers Steel, a leading researcher, that procrastination is 'irrational' delay, in other words, we do so when we know we are acting against our own best interests. However, psychologists don't agree about what causes our irrationality. Is it dark thoughts, behaviours and personality traits? Compulsiveness? Unconscious death anxiety? Some say the cause is over-indulgent parenting, while others claim it is over-demanding parenting.

Although there is no consensus about what causes it, the dominant view has become that it is somehow our fault and that its perils pose a serious threat to modern society. Joseph Ferrari, a psychology professor at DePaul University, Chicago, calls procrastination a 'serious problem' and argues that we don't take it seriously enough. Jane Burka, the psychologist and author, says procrastinators are people who fear failure, success, or being controlled: "It's a way of protecting yourself from having your true abilities evaluated."

More books on Mind

Some people even call procrastination a disease, a mental disorder related to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, bipolar illness, obsessive-compulsive disorder, sleep problems and brain and thyroid anomalies. Not surprisingly, if procrastination is viewed so negatively, treatments will be designed to eradicate its presence and influence.

But we don't need to take such a draconian approach. Although the procrastination scaremongerers have run an effective public-relations campaign, the truth is that there can be real benefits from putting tasks off. Not every e-mail requires an immediate response. Not every closet has to be cleaned every day. Two of the skills that many students develop in college are the ability to manage their time throughout a semester and the ability to cram for an exam or quickly finish a term paper at the semester's end. Students who finish an assignment every week might not develop these skills.

We prize efficiency, but often effectiveness is more important, whether a decision is fast or slow. Surgeons benefit from checklists that force them to pause at various points during a procedure. Professional athletes who play sports that require super-fast reactions (eg, tennis, cricket, or baseball) benefit from waiting until the last possible millisecond to hit a ball. The most successful investors, such as Warren Buffett and Bill Ackman, will delay investment decisions for a decade, until they see a 'fat pitch' bargain. Procrastinated apologies are more effective than instant ones because they give the aggrieved party a chance to understand precisely what the wrongdoer has done and then vent - all before the apology itself. All too often, our snap reactions are wrong; biased by our ancestral hardwiring. That is why many successful professionals follow the adage, "Don't just do something. Stand there."

Paul Graham, a computer programmer, investor, writer, and painter, says, "The most impressive people I know are all terrible procrastinators. So could it be that procrastination isn't always bad? Most people who write about procrastination write about how to cure it. But this is, strictly speaking, impossible." When I worked on Wall Street, I was constantly faced with thousands of tasks I arguably should have done. If I had tried to do all of them, I would have gone insane - and I would have failed anyway. You might think trading derivatives requires quick responses, but in fact the most successful traders are those who are able to avoid the quick response. One hedge fund manager I interviewed told me he doesn't give his junior employees access to real-time price information because they would be glued to their trading screens, like teenagers playing video games. Instead, he sounds like an old-style parent: he wants his employees to read and think.

Paul Graham notes that when we procrastinate we don't work on something. However, we are always not working on something. In fact, whatever we are doing, we are by definition not working on everything else. The issue is not how to stop procrastinating, since we will always be not working on something, and thus procrastinating. Instead, our real challenge is to figure out how to procrastinate well; how to work on something that is more important than the something we are not working on. What matters most is comparing what we are working on with what we aren't.

If we aren't working at all, we are being slothful. If we are working on something unimportant, we are showing bad judgment. But if we are working on something important, then why judge us negatively for not working on something less important? If we put off errands because we are trying to cure cancer, are we really procrastinating? And if that is the meaning of procrastination, why is it so bad?

Those of us who feel guilty about procrastinating should ask ourselves whether there might be a good reason not to act right away. What are you doing instead of planning that dinner party? And which items can you move from your daily to-do list to a to-do list for a week from today? Several successful senior executives I interviewed for Wait told me that if they simply took everything in their in-box and moved it to their out-box they would have done the right thing 99 per cent of the time.

One crisp autumn day in 2005, senior executives from Lehman Brothers were summoned to a decision-making masterclass at the New York Palace hotel on Madison Avenue. Joe Gregory, the bank's president, reportedly hired a string of psychologists and business professors to talk about the benefits of snap decision-making and reliance on gut instinct.

Less than three years later, the bank went bust and thousands of employees were left jobless.

Was there a link between the two? Quite possibly, says Frank Partnoy, former investment banker and the author of Wait: The Useful Art of Procrastination. "I found it shocking that Lehman Brothers had four dozen of its senior executives take this course. Then they marched across town and made the worst decisions in the history of financial markets," said Partnoy.

"Lehman advocated always going with your gut. Gregory apparently used to hand out copies of Blink [the book by Malcolm Gladwell extolling the virtues of rapid decision-making] on the trading floor. I wanted Wait to be the antidote to that kind of mentality."

The central tenet of Partnoy's book is that, amid the frenetic pace of modern life, most people tend to react too quickly. We don't, or can't, take enough time to think about the increasingly complex timing issues we face.

Part of the reason for this is that technology is all around us, speeding us up. We feel its pressure every day, at work and at home. The best business leaders are those who fight against it.

He said that the most effective leaders are those who resist the urge to make snap decisions and instead act more cautiously. Seniority should naturally lend itself to taking more time to make important judgments. If you think about the pyramid of an organisation, the expectation is that the most junior people need to respond instantly when they are asked to do something. They don't take time to contemplate or question the strategy, said Partnoy. More senior people have the ability to delay. They can take their time.

The first challenge is assessing how much time you have to come to a decision. There are basically two categories of business decisions: those that have clear deadlines and those that don't.

If you are in a public company and you have to report to shareholders at the end of the quarter, the most successful business executives have that date in the back of their minds and are preparing for that deadline. They have a lot of informal strategising and so forth, he said. But in terms of the final decision, he added, they want to make it as late as possible. You want to be able to incorporate into that decision everything that you possibly can. It's being comfortable with the idea that you can delay it until the last possible moment.

The decision-making process becomes more complicated when the chief executive does not have a strict deadline. Perhaps you're Sempra [the utility provider in San Diego] and your time horizon is 40 years because you are thinking about whether to build a pipeline. Or you are Exxon Mobil [the energy giant] and you are trying to figure out when you need to make a complete business switch from oil to natural gas.

In the past, taking time to consider fully the options was viewed very differently to how it is today, said Partnoy. Centuries ago, procrastination was considered an indication of wisdom and good judgment.

More recently, procrastination has received a less positive press. We started in the 1970s. There were the 'we've got to get it done now' management gurus, who made people feel really bad about not getting everything done immediately.

There are exceptions to the rule, said Partnoy. People in the professions - architects, accountants, lawyers, doctors and so on - have to manage their time and think about time.

The assumption should not always be that slow equals good, he cautioned - Some people find lawyers to be too slow, for example - but he added that it's not always about being slow. Doctors in the emergency room will be incredibly fast, but the doctors I interviewed said that if you have a minute to do something in the emergency room, you should not make a judgment until 59 seconds have passed. If your time world is one minute, you should procrastinate as long as you possibly can.

In his book, Partnoy points to several highly successful individuals who have a penchant for procrastination. One is Warren Buffett, the American investor, who has claimed one of the secrets of his success has been delaying decisions.

Buffett once said: 'We don't get paid for activity, just for being right.'

Books by Title

Books by Author

Books by Topic