Zealot

The Life and Times of Jesus of NazarethReza Aslan

Here are the most controversial claims from Zealot:

Jesus wasn't born in Bethlehem

Few argue that the Nativity is not a lovely story, especially when it's acted out in church Christmas pageants, complete with Mary, Joseph, and three gift-bearing kings, all in Bethlehem to coo over the newborn son of God. But Aslan writes that this story is simply a magical tale. It appears in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, but it's not mentioned by any of the other apostles. (The name Bethlehem does not appear anywhere else in the entire New Testament, save for a single verse in the gospel of John.)

Jesus the historical figure was more likely born and raised in Nazareth - an off-the-map village in Galilee, Jerusalem, according to Aslan. "That he came from this tightly enclosed village of a few hundred impoverished Jews may very well be the only fact concerning Jesus's childhood about which we can be fairly confident," Aslan writes. Christopher Hitchens and others have noted that Matthew and Luke contradict each other when it comes to Jesus's genealogy and place of birth.

John the Baptist was once bigger than Jesus

The apostles reinterpreted John the Baptist's (in)significance in the gospels to make Jesus seem like the one and only messiah, according to Aslan. The scholar Josephus, who witnessed the destruction of Jerusalem, writes in Antiquities that John was put to death by Antipas, a first-century ruler of Galilee and Perea, because he was becoming too popular due to his promises of a new world order - the Kingdom of God. "Many assumed he was the messiah," writes Aslan, though you would never know it from reading the Gospel. John's baptism, according to Josephus, was "not for the remission of sins, but for the purification of the body." But Mark's Gospel says it was for the "forgiveness of sins" and that John recognized that "there is one coming after me who is stronger than I am, one whose sandals I am not unworthy to untie." The implication is that Jesus was the "one," though Mark never explicitly states that. Later Matthew would tell a slightly different story of John the Baptist and Jesus, in which John is the one who asks to be baptized.

So what accounts for these various discrepancies?

According to Aslan: "The problem for the early Christians was that any acceptance of the basic facts of John's interaction with Jesus would have been a tacit admission that John was, at least at first, a superior figure ... After all, who baptized whom?"

Jesus was a zealot revolutionary

The real Jesus was more like Che Guevara and history's other famous rabble-rousers than the passive love-thy-neighbor Christ figure in the bible. It's not clear why Jesus left Nazareth for Judea and John the Baptist, but when he returned, his transformation from craftsman to self-declared prophet was not entirely well received. So he established his ministry in Capernaum, a nearby fishing village, which, like Nazareth, was divided between the haves and the have-nots. The Capernaum have-nots did not know about Jesus's past life as a craftsman, and they were desperate for a better life.

Aslan writes that Jesus targeted those who found themselves cast to the fringes of society, whose lives had been disrupted by the social and economic shifts taking place throughout Galilee. He plucked a select few from the masses to be his disciples (the Gospel of Luke says he had 72 total, though there were only 12 in his inner circle). Like many revolutionaries and religious figures, he was beloved not just for his teachings, but for the charismatic zeal with which he delivered them - "as one with authority and not as the scribes," according to the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke. Unlike the rich priests, he seemed to a man of the people, a gift from God.

He was crucified for effectively committing a capital offense

When Jesus marched into Jerusalem around A.D. 30, flanked by a chorus of followers singing, "Blessed be the coming kingdom of our father David!" he was announcing himself to the city as the messiah and descendent of David, King of Judah. Then, like a true revolutionary, he forced the city's vendors out of the temple's public courtyard - a blatantly criminal act, Aslan writes. "After all, an attack on the business of the temple is akin to an attack on the priesty nobility, which, considering the temple's tangled relationship with Rome, is tantamount to attack on Rome itself."

With that sweeping gesture, Jesus's message was simple: the land didn't belong to Rome but to God, and it was time for Caesar to concede power to Hossana, the real King of Jews. This was sedition and the punishment was crucifixion. The New Testament says Jesus's crucifixion was a cruelly special punishment for a man who sacrificed himself for humanity's sins, but history tells us that he was no different from any other criminal who hangs on a cross.

Jesus didn't condone violence, but he didn't avoid it at all costs, either

Jesus's aggressive 'cleansing' of Jerusalem's temple is unlike the peacemaking Christ we know from the Bible - the one who invariably loved his neighbors and turned the other cheek in the face of violence. For starters, there is no evidence that these references are symbolic to all of mankind, but rather that he was speaking only about his Jewish neighbors and enemies.

Add to this that his entire ministry was constructed around the promise - specifically his promise - of God's sovereignty on earth, and we can only assume that Jesus expected bloodshed before this foundation for a new world order was laid, Aslan writes. Why else would he have warned his disciples that they, too, would "take up his cross" if they chose to follow him? As Aslan points out, his attempt to hide his "messianic secret" about the Kingdom of God from everyone but his disciples indicates that he knew what was to come - that what he envisioned was so radical, so dangerous, so revolutionary, that Rome's only conceivable response would be to arrest and execute them all for sedition.

We do have plenty of historical accounts of Jesus's miracles

Jesus helped the blind see anew, healed the infirm, and performed exorcisms. Or at least there are more historical documents claiming he did these things than there are those pertaining to his birth or death. But that says more about the time than it does about this specific miracle worker. Back then, he was one of many magicians wandering the region.

As Aslan puts it: "How one in the modern world views Jesus's miraculous actions is irrelevant. All that can be known is how the people of his time viewed them. And therein lies the historical evidence." One thing is true of both Aslan's Jesus and Christ: neither took payment for performing a miracle.

More books on Religion

Many of those who attended Aslan's reading Tuesday, including McLean, hadn't heard of the author before Fox's clip. By the time they stuffed into the room, though, it was clear that they had not only heard of him, they'd been reading his book. Powell's was all sold out of copies, came another announcement over the PA. Fox News's attempt to hammer him on television could not have backfired more supremely.

Aslan seemed to enjoy that.

"As you know, I'm here to talk about Islam," he opened, to a roar of laughter. Acknowledging the television cameras scattered about the room, he said "Most of you know you've walked into a taping of the Shahs of Sunset. Turns out, people are interested in Jesus. Who knew?"

"If I do have some kind of philosophical objective - behind my secret Muslim objective - I want to show people you can be a follower of Jesus without necessarily being a Christian."

Aslan then skipped reading a passage from his book - "readings are boring" - offered a brief background on his life, which included his time in an evangelical youth group, being blown away the first time he heard the Gospel at 15 years old, and preaching it to all of his friends after converting to Christianity. He later converted back to Islam, but remained fascinated by the story of Jesus, "who took on the greatest empire the world has ever known [Rome] in the name of the outcast and the marginalized and the dispossessed."

Wait, I thought this guy hated Jesus. I came here to shout at him! He called him a mean word in that there book I ain't actually read!

Yeah, that's the thing. Aslan's book may disagree with the Gospel's description of Jesus as a pacifist - Zealot describes him more as a 'revolutionary' - but that's not a bad thing, he stressed.

"That's a pretty cool guy," Aslan said. "That's a guy I want to know. Hopefully it's a guy you want to know. If I do have some kind of philosophical objective - behind my secret Muslim objective - I want to show people you can be a follower of Jesus without necessarily being a Christian."

Then, Aslan took questions, and something extraordinary happened. No one in the room grilled him about whether he had any business writing a book about Christianity. They actually asked him about the book itself. And the scholar did a pretty remarkable job of explaining his viewpoint on history in a lucid, funny, self-deprecating, and engaging way.

The reason people think of Jesus as a pacifist, and the reason they often forget that he was Jewish, is because that's actually how he became known as the true Messiah, the Son of God. The real Jesus was challenging the mighty Roman Empire's occupation of Jerusalem, and like the dozen or more other Jewish men declared 'messiah' by their disciples, he was ultimately murdered for it. The other messiahs' followers 'went home' at their deaths, Aslan said, because the fact that these so-called messiahs died instead of re-creating the kingdom of David meant they were disqualified, by definition.

"Jesus was a Jew, remember," Aslan said, "and according to Judaism, 3,000 years of Jewish Scripture and thought and philosophy and theology, a dead messiah is not the messiah anymore."

The difference with Jesus, Aslan posits, is that a different kind of Jew took up his story; the Diaspora, the wealthy, cosmopolitan, Hellenized Jews that had the resources to be able to travel to and fro places like Rome and Jerusalem and who, thanks to longtime exposure to Greek and Roman philosophy, could buy into the concept of a godlike man.

"It kind of makes sense to them, actually," Aslan said. "They start to adopt it, and as a result, something very interesting happens. The Hellenists are ultimately kicked out of Jerusalem for preaching this message, and the more they preach it in this Greek and Roman culture, the more Greek and Roman the message becomes. The less Jewish the message becomes."

As Jesus's story becomes less and less Jewish, descriptions of him become more and more pacifist, Aslan said. Writers of the Gospel made a conscious decision to continually downplay not only his Jewishness but also his revolutionary zeal. They were trying to convince the very people Jesus had worked so hard to overthrow, after all.

"Look, if you're a Christian in 70 C.E. [A.D.], and you want to continue preaching this gospel, you don't want to keep preaching it to Jews," Aslan said. "Do you really want more Jewish followers? The Jews are a pariah. What you really want to do is preach it instead to the Romans."

The crowd in Powell's was rapt - when it wasn't doubled over in laughter. Aslan's only reference to Fox News interview was in a discussion about Pontius Pilate, that guy who authorized Jesus's crucifixion, and in making the point that Pilate was actually yanked from his post as governor of Jerusalem by the Romans for executing too many dissident Jews.

"It's like when Fox News fired Glenn Beck," Aslan said. "'You are too crazy for us.'"

Aslan's only (direct) reference to the sensation he has become was in response to a question about the negative reviews he has received on Amazon from people who also clearly haven't read a word of Zealot. The author said the negative comments in that 'troll bomb attack' by 'these six Islamophobes living in their mothers' basements with, like, hundreds of fake Amazon handles' didn't bother him. In fact, he enjoyed that so many devout Christians had come to his defense, especially those who had taken the time to understand that Aslan is not a Jesus hater.

(Religious Dispatches Magazine)

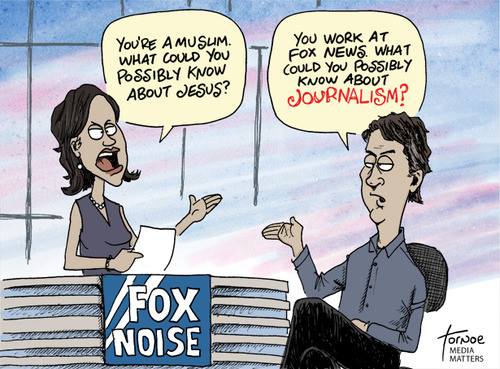

Unless you have been completely unplugged from all forms of media for the last week, you've probably seen - or at least have heard or read about - the interview that religion scholar, Reza Aslan, gave on the FoxNews.com webcast, "Spirited Debate" - or as Buzzfeed put it, "The Most Embarrassing Interview Fox News Has Ever Done."

If you haven't had the chance to see it, or if you aren't able to watch it now (below, right), here's what happened, briefly. The interviewer, Lauren Green, purportedly embarrasses herself by primarily asking Aslan not about the substance of his new book, Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth, but why he, a Muslim, could and would write a book about Jesus.

After Aslan calmly provides his credentials as a scholar of religions, Green, apparently unsatisfied with his answer asks, "But it still begs the question, though, why you would be interested in the founder of Christianity?" Again, Aslan informs Green that the objectivity necessarily held by a scholar entitles him to write about anything and anyone and expect a modicum of respect as long as the subject matter falls under his discipline and that the scholarship is sound.

Attempting to fight fire with fire, Green then trots out the criticisms of Zealot lodged by Christian scholar and apologist, William Lane Craig, and Christian pastor and journalist, John S. Dickerson (on Fox News). Craig classifies Aslan's book as unoriginal and flat-out incorrect in its labeling of Jesus as a Zealot. It's "nothing new under the sun" that will add little to the story of Jesus - a fate met by all previous attempts to get at the historical Jesus. Dickerson accuses Aslan of purposely misleading his audience by hiding his Muslim identity in order to claim objectivity as he dismantles the orthodox Christian story. Aslan responds in the interview solely as an academic - inviting criticism, citing his repeated candor about being a Muslim, and then clamoring for a discussion of the substance of his book.

On one level, the fact that the video clip has gone viral (4.8 million views on Buzzfeed and over 2.8 million views on YouTube at the time of this writing) is surprising. Bill O'Reilly has more forcefully shown his Christian bias in interviews, especially with British evolutionary biologist, Richard Dawkins. And Aslan had to know that a Fox News interviewer wouldn't fawn over his findings and nod with approval, as was the case on The Daily Show and NPR. On another level, the ability of this video to provoke such a visceral response from viewers - and hence be passed around to those with similar outrage - shouldn't surprise us at all. It’s compelling, especially to those who side with Aslan, for several reasons.

We may be well aware of the political bias that colors the journalism at Fox News, yet for Green to foreground her religious bias in an interview with a bona fide scholar of religion (unlike O'Reilly’s aforementioned interview with Dawkins, a biologist) is beyond the pale. In addition, Green's thinly-veiled Islamophobia is contrasted with the calm demeanor of a Muslim who proposes that had she read the book, she may have been pleasantly surprised at his conclusions about Jesus.

A classy, statesman-like takedown of an ethnocentrist at best (a bigot at worst) always sits better with the agreeable audience. The interview also exposed a double-standard—Green interviewed Christian professor Barry Vann about his book, Puritan Islam, without a hint of incredulity. This kind of inconsistency gets The Daily Show writers furiously typing. Those on Green's side could gain satisfaction in the holes poked in Aslan's statement of his credentials. His doctorate is in sociology of religion, not in the history of religions, as he claims, though he began his doctoral work in history of religions. It also must be said that the interdisciplinary nature of religious studies trains one to be at home in varied fields of study.

A more hidden reason for the captivating nature of the video lies in the type of battle going on before our eyes. Many of us want to see the scholar vs. the dilettante; the open-minded vs. the close-minded; the objective vs. the subjective; the facts vs. values. More to the point, the interview presents us with a real shot at projection: we finally get the chance to stick it to Fox News, especially as it shows itself to be less than 'Fair and Balanced.' Aslan made it through the looking glass at which many of us have merely thrown our remote. And when he gets there, he says what we've always wanted to say if we were only given the chance. The fact that Fox News and the mass media profoundly shape the way Americans view religion irks the scholar toiling away on a book that will barely register on the religion Richter scale. Maybe, just maybe, Aslan can begin to right this ship.

In a more serious tone, Omid Safi sees Aslan's response as a step towards "dismantling the privilege" enjoyed by Christians in American culture as expressed by Green's implication that only Christians can talk about Jesus (or Islam or terrorism, or that only Republicans can write about Reagan). So, in addition to contending with the Islamophobia at work in this particular case, Aslan is attempting to establish the authority of the academic outsider in matters of religion over and against the authority of the religious insider who still possesses cultural ascendency in the United States. Safi is right, but there's another aspect of privilege being demonstrated here that plagues scholars of religion in particular.

There may be a deep distrust of academics held by some Americans, but organic chemistry professors aren't asked to state their personal biases before speaking. Cultural anthropologists have a long history of grappling with the insider/outsider problem, but it's more of a methodological/hermeneutical issue - is it truly possible for an American to understand a Mayan corn dance?

A different scrutiny is applied to the work of religious studies academics (who have their own insider/outsider dilemma) because almost everyone they meet is a self-proclaimed expert in religion. What should we make of one commenter's remark on the Aslan video: "Religion scholar. . . isn't that an oxymoron?" This presumes that expertise in one's own religion - or one's own rejection of it - is earned without pursuing degrees. According to this view, academic training only pushes the budding scholar farther away from "real" Christianity, as Green calls it.

And as Aslan found out, the scholar's 'objectivity ID card' must be shown over and over, though the suspicion of a hidden agenda never goes away. He feels compelled to point out that his mother, wife, and brother-in-law (an evangelical pastor) are Christians to further separate his own faith from the aims of his scholarship. Whether in the classroom, at the dinner table, or on the ski lift, telling someone that you study religion is most often followed with, "Which one?," as though a singular answer would pacify the interrogator. And if the conversation begins to go down the path of a Green-like interview, wouldn't all academics state what they really do in response, just as Aslan did?

Of course there is no true Archimedean point from which to sit in these matters. Aslan chose to write about Jesus because he's been obsessed with him for decades. One might want to ask whether this book was perhaps an attempt, subconsciously or not, to get over old resentments or heal old wounds. While he should not have to answer these ad hominem questions, the repeated recitation of his credentials doesn't serve to highlight his qualifications so much as it reflects the fact that, as he wrote in an open discussion on Reddit, he already knew that writing about Jesus or religion in general would raise concerns: "I had some indication of what was about to happen from the attack piece they did on me a few days before the interview. I assumed that we would deal with that at first and then move on to the book. It was only about half way thru that realized what was happening." This is why the interview was not a debate over the real historical Jesus but over who has the right to make claims about Jesus and what gives him or her that right.

If an overwhelming majority of viewers side with Aslan over Green/Fox News, then what did 'we' win? In one sense, both Aslan and Fox News won: Zealot has shot up to the top of the Amazon Best Sellers list, and Aslan is reveling in his good fortune, while many who'd never heard of Lauren Green are likely to tune in (or, more accurately, log on) to cheer the next time she scolds a non-Christian, or to feel smug satisfaction the next time she embarrasses herself.

But in another sense, both sides lost. While the interview increased Aslan's book sales, the episode only reinforces the notion that scholars must rely on controversy to do so. And while displays of Christian privilege may provide a temporary bump in traffic, the network is only doubling down on a strategy with questionable long term prospects.

Because the authority to talk about religion was at issue here, thankfully the interview never slid into a tired debate over whether or not Jesus was divine. Even though no mutual understanding was reached, the role of religious studies scholarship, as opposed to the theological, was put on a grand stage. No doubt, Aslan and religion scholars, especially in America, will continue to be asked to show their papers. Yet, perhaps the conversation at the next family reunion will start with "Have you seen the Reza Aslan interview?" instead of "What gives you the right to talk about my religion?" We can only hope.

(New Yorker)

Being attacked for insufficient Jesus-ness by a Fox News anchor is apparently (well worth keeping this in mind) a way to drive your book up to No. 1 on Amazon, where Aslan's landed this week, before then landing, in turn, in our lap. Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth turns out to be a pugnaciously written, unduly self-assured, and, on the whole, extremely conventional view of the historical Jesus, already familiar to those who keep up with contemporary Jesus studies. Basically, Aslan's work, though original in detail, echoes the conclusions of the writer and scholar John Dominic Crossan in its vision of a peasant cynic Jesus: a rabble-rouser, a political radical, and an extreme Jewish nationalist - a Zealot, who infuriated the Romans and got the horrible Roman punishment for insurrection. This Jesus ran a kind of family-cult synagogue in Jerusalem, which was passed on to his brother James, who then got mostly written out of the record after Paul's more Roman-friendly Christianity took the stage.

As always in these things, the interpretation involves picking out some texts as core while dismissing others as late or interpolated, with the criterion for choosing between them seeming to be, more or less, whether stories float your boat rather than what truths can be shown to walk on water. If you privilege the radical, Zealot Jesus - the one who eats with prostitutes and dismisses kosher diets and rails against Caesar - you have a hard time explaining the unworldly, Sermon on the Mount Jesus, and a still harder time explaining the purely hieratic, apolitical non-human savior-from-heaven Jesus who emerges in Paul's letters in the decades after Jesus's death. If you like the messianic son-of-man Jesus, you have a hard time explaining what it was that riled up the Romans. If you go for the angry activist Yeshua who drove the poor money changers from the Temple (many of them no worse than the kinds of currency-exchange folks you see at airports), you have a hard time explaining how he emerged so quickly as Paul's Christ, a figure so remote from politics or life itself - no personal stories with wise sayings - as to lead to the rational suspicion that Paul did not intend to indicate anyone of earthly existence at all.

In either case, you have a hard time explaining why such a memorable figure left so faint a footprint on the sands of his own time. Josephus, the great and sure-footed Jewish historian of the period, most likely never mentioned him at all. (A vexed question in ancient historiography is whether the one extended reference in Josephus to Jesus is a later interpolation or has a 'residue' of original intent. If there is a residue, it is that of a wonder-worker, but not of a Zealot, a type Josephus mistrusted. There's a second reference to that brother, James, but it's disputed, too.)

'Jesus' may be a compound figure, to whom tales and truths of many kinds have been ascribed. It's also perfectly possible, as I've suggested in the magazine, that the original figure, assuming there was one, actually was this varied, or nearly so: charismatic leaders of oppressed peoples tend to be plural in character to the point of self-contradiction. Was Malcolm X a violent radical nationalist or an embracing universalist? It depended on what moment and in what mood you caught him. The same is true even of Nelson Mandela. It wouldn't be hard to imagine a historian two thousand years from now arguing that the real Mandela was a fierce, vindictive prophet, with the conciliatory one a much later overlay.

Aslan, to his credit, is candid about the truth that Jesus the wonder-worker and miracle-doer is more prominent in the Gospels than any other Jesus. And as a scholar, he seems, implicitly, to subscribe to the one rational argument about all miraculous events: in billions of years of the earth's existence, there is not a single credible instance in which the laws of nature have been abrogated, but, in the sixty thousand years Homo sapiens have been around, there are innumerable instances in which people have made up stories about such abrogations to impress other people with the virtues of their favorite king or god.

Which returns us, as it should, to that interview. The odd thing about it is not the rage at the idea of a Muslim writing about Jesus, but the fact that there was no sense of embattlement. The utter incredulity, perhaps insisted on by the producer in Lauren Green's earpiece, was offered in a tone of self-evident disbelief: Who could even imagine that a Muslim could write about Jesus? What was really striking about Green's don't-come-to-Jesus moment was its equable complacency - ot fierce, argumentative anger, but a kind of bland, blank, bored congenial scorn.

This moment in history will perhaps become known as the Great Secession from Sense. The view that Muslims can’t speak of Jesus is of a piece with the view that it is actually a diminishment of liberty to ask people to buy health insurance, or that the more guns there are in the more hands the less gun violence there will somehow be. Views that in a normal polity would be regarded as the outer edge of the bizarre have become, in the sealed-off world of American zealotry, unexceptional, while those that should be entirely uncontroversial are marched out and subjected to absurd interrogations. By now, everyone is so benumbed that it takes the truly weird even to register at all.

Books by Title

Books by Author

Books by Topic