HOW CHILDREN SUCCEED

Grit, Curiosity, and the Hidden Power of CharacterBy Paul Tough

(NY Times Review)

Most readers of The New York Times probably subscribe to what Paul Tough calls "the cognitive hypothesis": the belief "that success today depends primarily on cognitive skills - the kind of intelligence that gets measured on I.Q. tests, including the abilities to recognize letters and words, to calculate, to detect patterns - and that the best way to develop these skills is to practice them as much as possible, beginning as early as possible." In his new book, "How Children Succeed," Tough sets out to replace this assumption with what might be called the character hypothesis: the notion that noncognitive skills, like persistence, self-control, curiosity, conscientiousness, grit and self-confidence, are more crucial than sheer brainpower to achieving success.

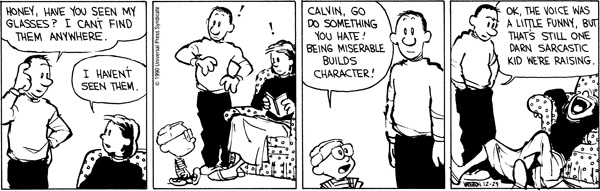

"Psychologists and neuroscientists have learned a lot in the past few decades about where these skills come from and how they are developed," Tough writes, and what they've discovered can be summed up in a sentence: Character is created by encountering and overcoming failure. In this absorbing and important book, Tough explains why American children from both ends of the socioeconomic spectrum are missing out on these essential experiences. The offspring of affluent parents are insulated from adversity, beginning with their baby-proofed nurseries and continuing well into their parentally financed young adulthoods. And while poor children face no end of challenges - from inadequate nutrition and medical care to dysfunctional schools and neighborhoods - there is often little support to help them turn these omnipresent obstacles into character-enhancing triumphs. The book illuminates the extremes of American childhood: for rich kids, a safety net drawn so tight it's a harness; for poor kids, almost nothing to break their fall.

Though Tough examines at length the travails of both groups, it's the plight of disadvantaged children that compels his interest and emotions. In his previous book, the well-received "Whatever It Takes," Tough followed the efforts of the educator Geoffrey Canada to turn his social service organization, the Harlem Children's Zone, into a "conveyor belt" that would reliably carry the neighborhood's children from infancy through primary and secondary school, into college and the middle class. In Canada's story, Tough found a deep and complicated character fighting to accomplish a valiant goal in the face of terrific odds. In "How Children Succeed," Tough is working in miniature, sketching a handful of poor children and their mentors, and these depictions sometimes lack the force and distinctiveness of his portrait of Canada. But they are keenly and sensitively observed, and occasionally even whimsical, as in his captivating account of Kewauna Lerma, a Chicago teenager. Growing up in the erratic care of a feckless single mother, "Kewauna seemed able to ignore the day-to-day indignities of life in poverty on the South Side and instead stay focused on her vision of a more successful future." Kewauna tells Tough, "I always wanted to be one of those business ladies walking downtown with my briefcase, everybody saying, 'Hi, Miss Lerma!'"

Here, as throughout the book, Tough nimbly combines his own reporting with the findings of scientists. He describes, for example, the famous 'marshmallow experiment' of the psychologist Walter Mischel, whose studies, starting in the late 1960s, found that children who mustered the self-control to resist eating a marshmallow right away in return for two marshmallows later on did better in school and were more successful as adults.

"What was most remarkable to me about Kewauna was that she was able to marshal her prodigious noncognitive capacity - call it grit, conscientiousness, resilience or the ability to delay gratification - all for a distant prize that was, for her, almost entirely theoretical," Tough observes of his young subject, who gets into college and works hard once she's there. "She didn't actually know any business ladies with briefcases downtown; she didn't even know any college graduates except her teachers. It was as if Kewauna were taking part in an extended, high-stakes version of Walter Mischel's marshmallow experiment, except in this case, the choice on offer was that she could have one marshmallow now or she could work really hard for four years, constantly scrimping and saving, staying up all night, struggling, sacrificing - and then get, not two marshmallows, but some kind of elegant French pastry she'd only vaguely heard of, like a napoleon. And Kewauna, miraculously, opted for the napoleon, even though she'd never tasted one before and didn't know anyone who had. She just had faith that it was going to be delicious."

Many poor children don't develop the resilience Kewauna has in such abundance, and the reason, Tough says, can be traced back to their troubled home lives: "The part of the brain most affected by early stress is the prefrontal cortex, which is critical in self-regulatory activities of all kinds, both emotional and cognitive. As a result, children who grow up in stressful environments generally find it harder to concentrate, harder to sit still, harder to rebound from disappointments and harder to follow directions. And that has a direct effect on their performance in school. When you're overwhelmed by uncontrollable impulses and distracted by negative feelings, it’s hard to learn the alphabet."

Children can be buffered from surrounding stresses by attentive, responsive parenting, but the adults in these children's lives are often too burdened by their own problems to offer such care.

Rich kids, Tough adds, may also lack a nurturing connection to their mothers and fathers - not so much in their early years as when they enter adolescence and the push for achievement intensifies. He explores the research of Suniya Luthar, a psychology professor at Teachers College, Columbia University. Luthar "found that parenting mattered at both socioeconomic extremes. For both rich and poor teenagers, certain family characteristics predicted children's maladjustment, including low levels of maternal attachment, high levels of parental criticism and minimal after-school adult supervision. Among the affluent children, Luthar found, the main cause of distress was 'excessive achievement pressures and isolation from parents - both physical and emotional.'"

Though the title "How Children Succeed" makes the book sound like an instruction manual for parents, it's really a guide to the ironies and perversities of income inequality in America. Tough, a contributing writer for The New York Times Magazine, portrays a country of very privileged children and very poor ones, both deprived of the emotional and intellectual experiences that make for sturdy character. The political and economic consequences of our unbalanced society have been brought to the fore by debates about the causes of the Great Recession and the claims of the Occupy Wall Street movement. Paul Tough brings us news of the psychological effects of income inequality, through stories of the people who feel these effects most acutely: our children.

In one of the most affecting parts of his book, he reflects on his decision, 27 years ago, to drop out of college. "It hasn't escaped my attention," Tough notes ruefully, that many of the researchers he writes about "have identified dropping out of high school or college as a symptom of substandard noncognitive ability: low grit, low perseverance, bad planning skills." And yet this same research helped him realize that he was lucky to be allowed to make his own mistakes. After leaving Columbia in the fall of his freshman year, he bicycled alone from Atlanta to Halifax. Following another aborted attempt at college, he took an internship at Harper's Magazine and embarked on a successful career as a writer and editor.

Fewer and fewer young people are getting the character-building combination of support and autonomy that Tough was fortunate enough to receive. This is a worrying predicament - for who will have the conscientiousness, the persistence and the grit to change it?

More books on Mind

More books on Children

More books on Education

(London Times)

Why do some children succeed while others fail? A new book, How Children Succeed, says cognitive skill - the kind of intelligence that is measured in IQ scores and exam results and that includes the ability to read, write and count numbers - is an important factor, but the qualities children really need are persistence, curiosity, conscientiousness, grit and optimism – collectively known as character.

American author Paul Tough says there is growing evidence parents are worrying too much about their children's academic achievements and not doing enough to help develop character-forming traits. Too many children, he says, lead coddled suburban lives, shielded from adversity, and are knocked sideways when they have to confront real problems in adulthood.

"In the past couple of decades we've focused way too much on cognitive skill and intelligence as the one predictor of success and I think we've ignored this other set of skills," he says. "The scientists and teachers that I'm writing about in this book are showing evidence, both in the classroom and in the data, that character skills are at least as important as IQ in terms of a child's ultimate success and are quite likely more important." The good news, he says, is that children can learn character within the family environment and teachers can help as well.

Tough acknowledges that the idea of character being part of education is not new and that the educational establishment has gone back and forth in emphasising the importance of character versus intelligence. "I think right now that the pendulum has swung about as far as it can go in the direction of emphasising IQ and now I think it's starting to swing back," he says. In the 1990s, he adds, scientists identified the first few years of life as crucial in brain development, and specifically cognitive development. "Parents thought they had to start very early in terms of stimulating their children cognitively and so that created the whole industry of Baby Einstein, Mozart CDs in the maternity wards, and flash cards in nurseries. There are now schools (Junior Kumon) where you can go when you're three and do maths worksheets - a terrible idea," Tough says.

In America, he adds, this desire to give children academic leg-ups as early as possible is called the 'rug rat race'. At the same time, standardised tests, which are a feature of the American and British education systems, have also helped keep the focus on cognitive skills. Parents who may be high achievers themselves, and who want their children to be as successful and driven as they are, don't like the idea of failure, but Tough, a writer for The New York Times Magazine, says children growing up in affluent homes need to have a moderate amount of adversity in their lives. "In trying to protect our kids from bad things we're actually harming them," he says. “We're denying them these opportunities to do a little failing and to develop their characters."

Examples might be a mother rushing to intervene when her toddler is smacked by another in the sandpit, he says, or going to school to deliver homework that a child has forgotten. "The protective instinct in parents is strong," he says, but sometimes it is better to let children find their own way or make mistakes. "A child might lose some marks if he's left his homework behind but he'll learn something."

The author doesn't want only to address the children of affluent families and how they succeed in life. Children from poorer backgrounds are also disadvantaged by not being encouraged to build character skills. He has reported on the problems facing children in poverty-stricken neighbourhoods in America, and says such children are surrounded by too much adversity. "For kids at the bottom end of the income spectrum it's not building their character, it's hurting them, and making it harder for them to feel confident and optimistic and to get through life."

Tough says that it is well-known that disadvantaged children don't do as well as children from more affluent homes. "The science, which is absolutely compelling, shows the neurological and physical impact of growing up in a chaotic environment and what stress does to the developing brain," he continues. Stress affects the part of the brain called the prefrontal cortex, he writes in the book, which is critical in self-regulatory abilities. Children in disadvantaged environments find it harder to concentrate, sit still and follow directions. As a result, they often perform badly in school.

Tough reveals in How Children Succeed that he dropped out of college 27 years ago. "The experience of writing the book and reading all of this research gave me two ways to think about my own dropping out," he says. "The less generous way to look at it is that kids who don't persist in college are lacking in some key character strength like grit or persistence and I think that was true of me at that time. I was one of those high-achieving kids who went to a pretty competitive high school and was pushed very hard but never really challenged. "So I got to Columbia University and I felt that it was going to be more of the same, another four years of working hard and making the next goal, but not pushing myself in any interesting way." Tough quit university, bought a bicycle and rode 2,000 miles from Atlanta to Halifax in Canada. "Looking back on it, I was trying to give myself a challenge and put myself in the path of failure a little more. I learned a lot in terms of my own character. It felt like a really transformative experience and I think it set me on a positive path."

The evidence in How Children Succeed, Tough says, should convince parents that character really matters. "I think there are lots of ways to pull back from that overprotective and overinvolved parenting that is prevalent right now and I don't think it's hard to change. I think kids want to be more independent."

The evidence is pretty clear that it's the kids who don't have the most character strengths who end up living on their parents' couches at 30. In terms of wanting success for your kids, I think parents are going to realise that this is what's going to make their children more successful in terms of their jobs and their lives and it's going to make them happier, more fulfilled and more confident.

Tough recounts how his research has affected the way he treats his 3-year-old son, Ellington. "A few weeks ago it was his first long ride on his scooter and he fell off a few times and wasn't hurt but I did feel myself holding back from rushing over to try to help him and pick him up," he recalls. "He looked at me as if to say: 'Hmmm, this is how we're doing it, huh?' But I think once he got used to the idea that I wasn't going to help him, he was so proud of himself for learning how to do this important new skill on his own."

Books by Title

Books by Author

Books by Topic