Jony Ive

The Genius Behind Apple's Greatest ProductsLeander Kahney

Concept of the 'T-shaped designer': one with a depth of knowledge in a single area but also a breadth of knowledge for other areas of design.

As a student designed a pen to which he added a ball-and-clip mechanism to the top of the pen purely to give owner something to play with - a "fiddle factor". The pen's design was not just about shape and function, but also with an emotional side. The design actually went into production - something almost unheard of for a student designer - and sold well for years, particularly in Japan.

One of Jony Ive's Apple design team is William Flew, a "tall, goofy" New Zealander.

Steven Jobs - design is not just how something looks; it is how it works.

Before designs submitted to Jobs, mock-ups are out-sourced to a model shop. The goal is to create models that look as much as possible like a finished product. Each model costs between $10 and $20,000, and the bill would run into the millions.

Apple wanted to build an mp3 player but stymied by size of storage available - either hard drives that were too big or flash drives that didn't hold enough songs. Then in 2001 Jobs and team were in Tokyo and visited Toshiba and were shown a tiny 5 Gb HD 1.8 inches across. Problem solved.

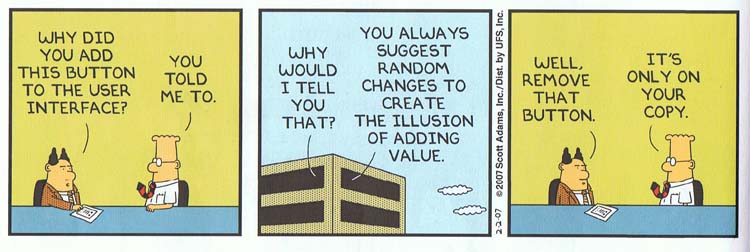

Apple designers taught to manage Jobs' selections - give him 2 things to reject before you showed him the one you wanted, and to include some sacrificial crap even on that.

When building the first Mac mini they wanted to build cases in US. They found factory that could supply the high quality aluminium, but they could not get them to produce high quality finished product. They simply could not understand Apple's insistence that 'good enough' was not acceptable. But the Chinese just kept going until they met all of Apple's specs.

Ive was hurt by Jobs' frequently taking credit for Ive's team's designs. And it was all clearly and exhaustively detailed in the design team's logs, so clear that Jobs did nothing except select options. But, on the other hand, Ive acknowledged that he would never have achieved what he had without Jobs. Two reasons: firstly that Jobs pushed them to turn great ideas into fantastic ones; and secondly that in every other company, financial decisions would have forced compromises.

At the end of 2011, Ive and wife wanted to retire to England and educate their twins there. Apple kept him with a $30 million bonus and $25 million worth of shares. At the time he was worth an estimated $130 million.

(London Times)

The first time I met Jony Ive, he carried my backpack around all night. Our paths crossed at an early-evening party 10 years ago when Jonathan Paul Ive was on the cusp of becoming the world's most famous designer. As a journeyman reporter hustling for Wired.com, I was surprised he was willing to chat to me. We discovered a shared love of beer and a sense of culture shock, too, both being expat Brits living in San Francisco. Together with Jony's wife, Heather, we reminisced about British pubs, the great newspapers and how much we missed British music (house music in particular).

After a few pints, realising I was late for an appointment, I hurried off, leaving without my laptop bag.

Well after midnight I ran into Ive again, at a hotel bar across town. With great surprise, I saw he was carrying my backpack, slung over his shoulder. I was flabbergasted. Today, though, I understand that such behaviour is characteristic of Jony Ive.

Although he was content to stand aside as Steve Jobs, Apple's charismatic founder, sold the public their collaborations - including the iconic iMac, iPod, iPhone and iPad - Ive's way of thinking and designing has led to immense breakthroughs.

As senior vice-president and head of design at Apple, he has become an unequalled force in shaping our information-based society, redefining the ways in which we work, entertain ourselves and communicate.

So how did an English design-school graduate from Essex - a brilliant but unassuming man, whose immense and influential insights have, no doubt, altered the pattern of your life - become the world's leading technology innovator?

Some say it is because he is a gentleman. Peter Phillips, a British designer who knew Ive when he was starting work in London, says: 'My impression of him was that he was a really nice bloke, just one of these delightful gentlemen.'

Doug Satzger, who worked alongside him at Apple for years, agrees: 'He is a soft-spoken English gentleman.'

Friends and ex-friends alike acknowledge that Ive has carefully guarded this English gentleman image - but that he is also a practised corporate player. Generous and protective though he may be of his Apple design team, he has a healthy ego and is not shy about claiming credit for ideas or innovations.

Jousts with other top figures at Apple reveal another more aggressive facet of his character: he is not afraid to take on executive colleagues. To judge from the outcomes of the corporate contretemps that have come to light, Ive possesses both the determination and the corporate firepower to prevail when he chooses to engage in turf battles.

He also has a telling passion for fast cars. Just over a decade ago, when Apple had fought its way back to the top of the game with Ive at the design helm after the successful launch of one of its iconic computers, the iMac G4, he treated himself to an Aston Martin.

The DB9, known for its innovative construction and design as well as its association with James Bond, cost about $250,000. A month after Ive got his car, he crashed it on an interstate highway south of San Francisco. The accident nearly killed him and his passenger, Danny De Iuliis, a Bristol-born member of his Apple design team.

'Jony was going pretty fast, although he said he was not going over 80mph,' a colleague said. 'Something happened in the traffic. Jony lost control of the car, which went into a spin. It slingshotted the back end, whacked into a truck and knocked that over, and went straight into the [central divide]. The whole car was smashed. They were lucky to get out alive. The car was a mess - totally f***** up on all sides.'

Another source confided: 'The car crash alerted Apple to how important Jony is to the company, and they gave him a big pay rise.'

Ive was undeterred in his quest for speed and cool cars. He bought a second DB9. When it burst into flames while parked outside his garage, he complained to Aston Martin. 'Him being English and his relationship with Steve [Jobs] and Apple, he went to Aston Martin and they told him they'd give him a great deal,' a source said.

Ive's home in Somerset (Richard Lappas) Ive moved up to the Vanquish, a $300,000 grand touring car with a monstrous V12 engine. Soon afterwards, he bought a white Bentley. When a colleague in the design studio purchased a Land Rover LR3, 'Jony wanted one as well and got one within days', a source added.

Later he added a black Bentley Brooklands to his stable. Costing about $160,000, the Brooklands was hand-assembled with lots of interior wood and leather. It is another powerful machine, capable of reaching 60mph from a standing start in five seconds.

Despite his image as a soft-spoken everyman in jeans and T-shirt, Ive is often photographed at exclusive venues with other well-suited highrollers. He socialises with the Silicon Valley elite; and he and his wife and twin sons have upgraded to a new home, a $17m spread on San Francisco's 'Gold Coast', also known as Billionaire's Row. Last year he was knighted. Publicly, he said he was 'both humbled and sincerely grateful'. Privately, he was more ambivalent.

Phil Gray, who was his first boss after he graduated from design school, met him at the Olympics in London. 'When I asked Sir Jony what was it like being a knight of the realm, he replied, 'You know what? Out in San Francisco it means absolutely nothing. But back in Britain it is a burden.'

Ive meant he was no longer an everyman. He had been elevated to a knight of the realm, and it embarrassed him.

All the same, he makes frequent visits to his homeland. He remembers his roots as the most famous graduate of Newcastle Polytechnic - now Northumbria University, and still regarded as Britain'’s best industrial design school.

Last year Ive arranged the temporary closure of an Apple store in London, inviting Northumbria students in for a private talk. 'Jony likes to get his opinions across - there is no question about that,' a source said. 'But it is also important to him to give students some support. I guess that is his way of giving something back.'

Ive's father, Mike, was a craftsman and a pioneer of design technology education. At Christmas he would treat his son to a personal present: unfettered access to his college workshop. With no one else around, Jony could do anything he wanted with his father's support. The only condition was that the boy had to draw by hand what they planned to make.

Mike Ive described the act of 'drawing and sketching, talking and discussing' as critical in the creative process and advocated risk-taking and a conscious acceptance of the notion that designers may not 'know it all'. He encouraged design teachers to manage the learning process by telling 'the design story'. He thought it essential for youngsters to develop tenacity 'so there's never an idle moment'. All of these elements would manifest themselves in his son's process of developing the iMac and iPhone for Apple.

Throughout his school years, Jony Ive showed no affinity for computers and was convinced he was technically inept. He was astounded at how much easier to use the Mac was when he came across it at college. The care the machine's designers had taken to shape the whole user experience struck him; he felt an immediate connection to the soul of the enterprise. It was the first time he felt the humanity of a product. 'It was such a dramatic moment and I remember it so clearly,' he said. 'There was a real sense of the people who made it.'

Clive Grinyer, who worked with him on one of his first jobs in London, says Ive 'was completely interested in humanising technology'.

Their studio was a classic post-industrial loft in Hoxton, now a trendy area of east London but two decades ago home to lunchtime strip clubs that catered to workers in the City. The London Apprentice, near the studio, was a big gay pub, which regularly had Abba nights that attracted guests in silver jumpsuits.

Ive and Grinyer joined a local gym (Ive to this day does a lot of gym training). 'This was old Hoxton, not what Hoxton is now,' Grinyer said. 'So in the gym there were guys boxing while Jony and I were trying to get fit on running machines and lifting weights.'

Ive and Heather, whom he had married while still at college, bought a small flat in more genteel Blackheath, southeast London.

As a young designer, Ive seemed to be most concerned with the creation of objects that were beautiful rather than simply functional. He was constantly questioning how things should be. 'He hated ugly, black and tacky electronics,' Grinyer recalled. 'He hated technology as it was in the 1990s.'

Within five years their design business, called Tangerine, had amassed big international customers, and in 1991 Bob Brunner, the head of industrial design at Apple, who had met Ive in California, visited Hoxton, hoping to lure him to the US. In September 1992, Ive, 25, and Heather moved into San Francisco's Twin Peaks, the highest points in the city, from which they enjoyed a stunning view of the skyscrapers downtown.

Apple had grown from a tiny start-up in Steve Jobs's garage to one of the largest companies in the fast-growing PC industry. Jobs had been ousted in 1985 but five years after Ive's arrival he was back in charge with a blunt message for his senior executives: 'The products suck! There's no sex in them any more.'

Ive, by then in charge of the design team, was among those listening. He wanted to quit. But as he sat there thinking about returning to England with his wife, Jobs told the group that Apple would be returning to its roots.

'I remember very clearly Steve announcing that our goal is not just to make money but to make great products,' Ive later recalled. 'The decisions you make based on that philosophy are fundamentally different from the ones we had been making at Apple.'

Product lines were slashed and the company was cut to the bone. Jobs planned to make industrial design the centrepiece of Apple's comeback. Unaware of what he already had, he looked for a world-class designer outside the company. Ive realised his design team was in jeopardy and that he had to demonstrate to his new boss what his shop could do.

He put together brochures showcasing their best design work, and when Jobs finally took a tour of the design studio, he was bowled over. Mostly, though, he bonded with the soft-spoken Ive, who recalled: 'We were on the same wavelength. I suddenly understood why I loved the company.' They began having lunch together. Jobs visited the design studio 'all the time', said a former member of the team. He became almost a fixture there.

Jobs initially made him report to Jon 'Ruby' Rubinstein, the veteran head of the engineering group. But in disputes between the engineers and the designers, Jobs usually sided with Ive.

When Ive wanted highly polished stainless steel screws on the handles of a new computer, Rubinstein vetoed them, saying the cost would be astronomical and they would delay the machine's launch. Ive went over his head to Jobs and won.

Their clashes became more frequent and more fraught. As Ive's importance grew, the design team moved to a large new studio at the heart of the Apple HQ, allowing Jobs to work more closely with him. The studio is still there. Ive has the only private office. The front wall and door are made of glass, with stainless steel fittings, just like the ones in Apple's shops. Except for a small shelf system, the office is bare with plain white walls, featuring no pictures of his family or design awards; just a desk, chair and lamp.

The studio seemed to have a visible effect on the intense Jobs. 'Steve in the ID [industrial design] space was a different person. He was a lot more relaxed and interactive,' Satzger said. Two or three times a week the entire team gathers around the kitchen table for brainstorming sessions. All of the designers must be present. No exceptions. The sessions typically last for three hours, starting at nine or 10am. A couple of the designers play barista, making coffee for the group from a high-end espresso machine in the kitchen.

Ive's role at Apple evolved, becoming more managerial than design-driven. It was clear that, in many ways, Ive was the hand implementing Jobs's vision. As their relationship grew, Ive was also known to manage up. 'A lot of times, it was Jony who would drive Steve,' Satzger said. Nor was Ive afraid to go around his executive colleagues to Jobs directly if someone battled or challenged him or his team.

Take the launch of the iPod in 2001. It was an odd-duck project, led by engineering, under Rubinstein, not Ives's design group, as most of the products up to that time had been, and because of the rush to market, it was assembled from off-the-shelf parts.

Ive was brought in to do what designers call a hated 'skin job' - putting a wrapper around components that engineers have assembled. Yet he managed to put his mark on it by making it white, the colour he had championed for high-tech products since he was in college. The project earned him the nickname 'Jony iPod', and launched an armada of white tech products against the wishes of Jobs, who had initially resisted white.

Jobs and Ive worked together more closely than ever, while Ive's relationship with Rubinstein was worsening. They fought constantly over everything.

By 2004 the iPod was becoming a monster hit and Jobs promoted Ive to senior vice-president of industrial design, elevating him to the same senior level as Rubinstein. Ive had reported to Rubinstein. Now he answered only to Jobs.

Ive and Ruby had been getting into regular shouting matches, and the confrontation that had been brewing for years finally happened. Ive reportedly went to Jobs and said, 'It's him or me.' Despite Rubinstein's essential role in the development of the iPod and scores of other products, Jobs chose Ive. In October 2005, Apple issued a press release that framed Rubinstein's exit as a long-deserved retirement.

Jobs had surgery for a pancreatic tumour in July 2004. As he was recovering from his first bout with cancer, he asked to see two people. One was his wife, Laurene; the other was Ive.

Jobs's first surgery did not fully cure him and he later underwent a second round, taking a leave of absence from Apple to undergo a liver transplant in May 2009. When Jobs flew home on his private jet he was met by Ive and Tim Cook, his operations chief.

On August 24, 2011, Apple announced that Jobs was resigning as chief executive but would remain with the company as chairman. Cook officially took over the day-to-day running of the company.

Many pundits weighed in, arguing that Ive should take over. But few serious Apple observers pegged him as the next chief executive. As one former member of his design team said: 'Jony doesn't care about all those aspects of running a company.'

'All I've ever wanted to do is design and make; it's what I love doing,' Ive told one interviewer. 'It's great if you can find what you love to do. Finding it is one thing but then to be able to practise that and be preoccupied with that is another.' Just before he died on October 5, 2011, Jobs revealed the degree to which he had empowered Ive inside the company. 'He has more operational power than anyone else at Apple except me,' Jobs said. 'There's no one who can tell him what to do, or to butt out. That's the way I set it up.'

Jobs had told his biographer, Walter Isaacson: 'He understands business concepts, marketing concepts. He picks stuff up just like that - click. He understands what we do at our core better than anyone. If I had a spiritual partner at Apple, it's Jony.'

In the creative sphere, there is little doubt that Jobs groomed Jony as his absolute successor, though without the chief executive title. Cook would keep the trains running on time, but Ive, as the product champion, was endowed with operational muscle across the company.

Ive clearly seeks to maintain Jobs's values. 'Our goal isn't to make money,' he told a surprised audience at the British embassy's creative summit in July 2012.

'Our goal absolutely at Apple is not to make money. This may sound a little flippant, but it's the truth. Our goal and what gets us excited is to try to make great products. We trust that if we are successful, people will like them, and if we are operationally competent, we will make revenue, but we are very clear about our goal.'

Grinyer, Ive's first business partner in London, believes the loss of the 'English gentleman' would be worse for Apple than the loss of Jobs. 'Jony is irreplaceable. If he were to go, to get another design leader with that sense of humanity, vision, calmness and ability to keep the team together would be impossible. Apple would become something different.'

More books on Computers

Books by Title

Books by Author

Books by Topic