The Lives of Lucian Freud: Youth: 1922-1968

William Feaver

More books on Art

(Guardian)

Lucian Freud lived recklessly and selfishly - and made paintings unlike anything in the history of art.

Lucian Freud painted very, very slowly, requiring sitters to commit themselves to examinations that went on for hundreds of hours. In everything to do with making and looking at art, he proceeded fastidiously (a word he liked), with utmost patience and seriousness. In ways he generally declined to interrogate ("I don't do introspection"), this epic care was vitally related to the rapid abandon with which he ransacked his world for experience. The slow painter was in love with quickness and with risk. He lived with an improvisatory recklessness he would never have allowed himself in a brushstroke.

William Feaver has been thinking about this life for decades. A series of interviews in the 1990s grew into a settled rhythm of telephone calls most days. Freud (who died in 2011, aged 88) didn't want a biography published in his lifetime; for one thing, he liked to be furtive, not accounted for. But he chose to talk amply with Feaver, whose future book he preferred to call 'a novel'. Feaver was more interested in getting things down than making them up; with dictaphone stretched to the limits, he had the most superlative material - and he was bound to it. Large tracts of what we have here are Freud by Freud.

The first of two volumes, Youth begins with a jokily assertive boy in Berlin, and ends with a painter nearing his 50s, dedicating himself more than ever to his art. In between, it covers the enforced move to England in 1933, swaggering teenage arrival on the Soho club scene, art school in Suffolk, an adventure in the merchant navy, two marriages, much "getting up to things to do with girls", at least four "broods" of children, and many transits in the Bentley between low-life dives he loved in Paddington and high-life parties with Princess Margaret and debutantes he might take to Annabel's.

As a schoolboy at Bryanston he was already unruly, magnetic and doing detestable things. Refusing to make his bed (a maid's job), he inspired other boys to follow his lead. He positioned himself as a non-starter in lessons and went off to ride horses and draw. Neither Freud nor Feaver go looking for causes; both avoid the methods of grandfather Sigmund. Embarked spectacularly on being himself, the question of what he could do, each moment, in each unfolding situation, seems always to have gripped Freud more than why.

He discovered that he could do anything he desired. The force of his vitality drew people to him and put him in control. He would get the girl he wanted for the night even if it meant setting the Paddington toughs on her boyfriend. (The artist Joe Tilson, for this reason, was thrown down the stairs.) Guilt did not interest or waylay him. Shutting out his mother, whose devotion he did not want, was apparently no cause for compunction but simply what he needed to do.

His driving was dangerous and he kept it that way, impatient with any notion of safety. After hitting an ambulance at Hyde Park Corner, convictions accrued as the accepted cost of joyrides. When he gambled (horses, dogs, dice), the stakes were high; he had no interest in a flutter. He wanted "to change things with the bets", he told Feaver: "either be dizzy with so much money or otherwise not have my bus-fare". In horror, always, of middle-class security, he courted trouble that would put him on his mettle. He chose the company of fraudsters and burglars, whose resourceful gumption commanded his affection and respect.

Greedily appreciative of 'characters', hungry for crooks, beauties and heiresses, he arranged his own version of la comédie humaine. He always had time for Balzac, and felt affiliation with Henry Mayhew and Henry James. Yet for all the sense of panorama, the intensity he needed was bred in close quarters. He painted what occurred between the bed and the window in cramped hotels and between four walls at Delamere Terrace by the Grand Union Canal.

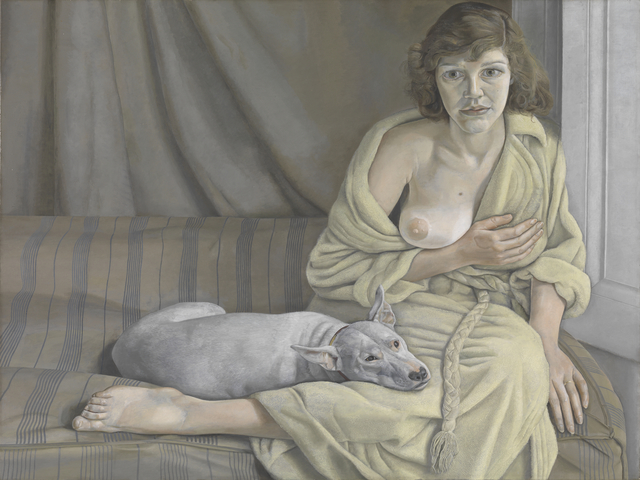

Painting was the thing that could not be two-timed, paid off or made to wait. As he refined his meticulously graphic style, he made pictures unlike anything by his contemporaries or in the history of art. Zebra-long lashes rimmed saucer eyes; clothes asserted themselves more insistently than the drapery of saints in Memling or Van Eyck. Then he loosened his brushstrokes, confounded his admirers, and made something new again, painting sagging, changeable, feeling flesh. In superlative accounts of the pictures, Feaver articulates their trapped, pinioned force: the couch in The Painter's Room standing daintily like a foal; Harry Diamond aggressively bewildered, squaring up to the palm tree in Interior at Paddington; Freud's 'burnishing of perspicacity' in a portrait of Peter Watson; his wife Kitty a nervous effigy in Girl with a White Dog - "This is an ordeal."

Hotel Bedroom was painted in Paris after marrying Caroline Blackwood, but that too was an ordeal. Finding the tie of wedlock off-putting while on honeymoon, Freud took up again with a former lover. "It was not a domestic life," Feaver offers. A brief attempt at establishing a marital home in Dorset looks, at least in retrospect, absurd. Freud spent a few distracted evenings at a Blandford Forum drinking club, went riding at night, and returned to London, leaving the housekeeper weeping at the treatment of "poor Lady Caroline". He was not offering monogamy, and most of the women who wanted him knew the deal. The ruthlessness was part of what drew them, though their voices are hard to catch here as Freud talks on.

There were many abortions and many children. He acknowledged 14 and knew there were others he hadn't come across. Some, at least, he was legally bound to support, and how could he afford it? The very question feels wrong-headed in the face of Frank Auerbach's view: "In a sense, his was a religious faith that these babies would be all right." They were not all all right, but we don't hear much about them. Since most of the children were marginal to Freud's life, they appear here only fleetingly. A few fragments float on the page. One of his sons gets two lines: "He and Suzy took the baby Ali on a trip to the Scillies once, by air. 'Flying over you could see the dolphins."

Feaver lets non-sequiturs produce their own effect. There's some fine judgment in the way he does this. Early on, I puzzled at the disparate events held together in paragraphs. In the teeming chapters of incident I kept expecting the arrival of a controlled narrative, questions posed and resolved, significant others brought sharply into focus. This biography does not work like that. So what is Feaver doing?

In a memorable 2013 essay, Julian Barnes discussed Freud as an 'episodicist' for whom 'one thing happens and then another'. His was not a linear view of life, concerned with connections and continuities. To an extreme extent, he acted on impulse, barely connecting one moment with the next. Every page of this volume affirms the distinction. No course of action on a Saturday (even marriage) affected his choice of what to do on Tuesday and Wednesday. Feaver replicates this episodicism in telling the life story. This is Lucian Freudian biography, packed with momentary stories and fundamentally resisting narrative.

As for Freud in his long 'youth': readers will reach their own views about the monstrous selfishness of the artist whose art is nonetheless a kind of gift. Feaver won't tell you what to think about it. To keep admiring the pictures and overlook the worst offences is no answer: better look long and hard. The life, like the art, may make you question what you know about the basic contracts of living.

(Atlantic)

I'd assemble myself on the love seat to mimic her position, plugging my left foot snugly between the cushions. I thought if I got it right, I, too, could enter such a pristine state of rest. (Alas, I remain a noisy mouth-breathing stomach-sleeper.) Only later did I learn that this was a reproduction of a Lucian Freud work titled Benefits Supervisor Sleeping (1995). The portrait - of a real-life woman named Sue Tilly - would sell for $33.6 million in 2008; it was, at the time, the most expensive painting by a living artist to be sold at auction. Freud's drive to reveal, even if it didn't quite take over in Norwich, gained him an audience, my young self included.

The years that Feaver covers start with Freud's birth (1922) and end when the artist is in his mid-40s, long before he paints Tilly. The biography can, in part, be read as a condensed transcript of Freud's and Feaver's phone calls, which took place almost daily over several decades - with the former's number always changing and the latter always the one to answer the call. The narrative voice, then, is often Freud's own, with Feaver's insights woven in. The reader learns how the artist spent these years: gallivanting around Europe, painting and partying and engaging in, as Feaver puts it, "various passions." (The phrase perhaps hints at Freud's propensity for turning muses into lovers, a dynamic that's recently been explored with acute specificity by Zadie Smith, among others.) At the same time, Freud was forming for himself an aesthetic doctrine that would remain conceptually intact until his death.

This doctrine first took shape at a lecture he gave at Oxford in May 1953 and was eventually published as 'Some Thoughts on Painting.' It begins: "My object in painting pictures is to try and move the senses by giving an intensification of reality." (Shortly before Freud's death, the art historian John Richardson would neatly sum up this notion by calling Freud's early paintings "more real than the real thing.") Viewers can see inklings of this extra-essenced style in Hospital Ward (1941), a work infused with the artist's own experience in the British Merchant Navy at age 19. Freud brings the dizziness of being at sea to bear on this painting of a boy in a hospital: An undulating brush makes waves appear lodged in his face, alluding to his particular form of war-weariness. The result is a portrait that reflects the boy's reality, as well as the sensory impact of those memories still lingering within him.

The idea that such free association might intensify a piece of art would continue to preoccupy Freud. More than a decade after Hospital Ward, in "Some Thoughts," the artist would explain that to achieve such an effect, a painter "must give a completely free rein to any feelings or sensations he may have and reject nothing to which he is naturally drawn." Freud goes on to invert the intuitive: In the pursuit of art, self-indulgence is not a luxury but, in fact, discipline.

The painter's critics tend to note the way these merciless aesthetic precepts bled into Freud's personal life, which involved endless and usually overlapping sexual affairs - often with his young, female sitters - and only intermittent attention paid to certain of his children. On this front, Feaver doesn't quite take his subject to task; instead he leaves his subtle imbrication of anecdotes and analyses up for interpretation. For a more personal perspective, readers might try Celia Paul's new memoir Self-Portrait, in which the artist chronicles, in part, her time modeling for Freud and the devastation his objectification and philandering inflicted: "I felt exposed and hated the feeling," she recalls of her time sitting for Freud. "I cried throughout these sessions."

Paul didn't meet Freud until she was his student at the Slade School of Fine Art in 1978, a decade after the years Feaver covers in this first volume, and one wonders what his second volume will make of her account (or of any other accounts from his muses, especially given the extent to which the age and power disparities would widen). If Feaver's approach in this first volume continues into his second, it's likely that not much will be made of it at all. While discussing the biography in a recent BBC interview, Feaver is asked what Freud was like behind closed doors. Feaver responded, in part, that over their long relationship, he noticed the 'wiles' Freud tried with young women were the same 'wiles' the artist brought to painting, to horses, to dogs, to friends and great art. "You can't see [Freud] as a predator, precisely," Feaver noted, "except that he was a predator of life in a most wonderfully wide-ranging way."

I wonder if Paul would have qualms about this characterization. While she "does not scorn the idea that gratitude can exist between muse and artist," as Smith put it, Paul nevertheless describes Freud's insistent stroking of her throat; his insinuations that a muse must yield completely to the artist ("He spoke admiringly to me," she writes, "of Gwen John, who had stopped painting when she was most passionately involved with Rodin, so that she could give herself fully to the experience"); and his eerie fondness for her sadness. In contrast, the idea of complicity permeates Feaver's book, particularly in his detailing of how Freud's friends, sitters, and kin - rather than find him predatory - largely seemed to understand the artist's project. For the most part, they were eager to be memorialized in, as Feaver writes, "paintings that held true."

This was the case, apparently, even under the most tender of circumstances, such as those behind Freud's Girl With a White Dog (1950-52). The portrait is the last Freud would paint of his first wife, Kitty Garman. In it, Kitty's chin, nipple, and breast appear defiant and vulnerable, each catching the pallid light from a nearby window. The white whippet on Kitty's lap appears to offer her the companionship that her husband failed to provide over their four-year marriage. The dog's eyes are raised, perhaps appraising Freud as he stood behind the canvas.

Freud explained to Feaver that in painting Girl With a White Dog, he captured "something that neither [he nor Kitty] were aware of before" - certain truths, including sadness and anger. His wife was pregnant in a "last bid," as she admitted to Feaver years later, to keep Lucian. Feaver writes of the portrait: "Expressive in its restraint, the painting is an exposure." According to Annie Freud, the couple's daughter, Kitty remained "very very proud of this painting" - proud of her boldness and fragility, and of her depiction as a real person.

But if Freud succeeded here, his myopia would seemingly prevent him from seeing others, such as Celia Paul, with the same fullness. In Painter and Model (1986), for instance, Freud at last portrays Paul as the artist she is. And yet her delicate features, so clear in Freud's earlier works, have been replaced with austerely set hair and a severe jawline. If this painting was an exposure, it only exposed, as Smith pointed out, Freuds pernicious blind spot: his inability to see that in this portrait he made the idea of feminine artistry and feminine beauty mutually exclusive.

The personal stakes surrounding Freud's paintings were not always so high, but the goal of hyper-reality remained constant. Finished the same year as Girl With a White Dog, Freud's Francis Bacon is arresting in its suggestion of panoramic corporeality, despite it being only a headshot. An elegiac energy roves clockwise around Bacon's face, which Feaver describes as "close, guarded, troubled, solitary really, and manifestly private." The portrait exemplified what Freud's second wife, Caroline Blackwood, called his "ability to make the people and objects that come under his scrutiny seem more themselves, and more like themselves, than they have been - or will be."

I can see now that it is this le plus quality that appealed to me about Freud's Benefits Supervisor Sleeping. It helps, as an adult, to watch videos of Sue Tilly describe her experience sitting for Freud as "absolutely amazing." Her delight infuses my delight. Looking again at the painting, you notice that Tilly's eyes aren't just closed; they're collapsed into their sockets. Her lips are more than shut; they're thoroughly sealed. Her body is not just limp, but also languid, as if its curled position is the sole shape it has ever taken. I, in turn, didn't want just to be asleep; I wanted to be asleep like Tilly - asleep inimitably.

Perhaps this quality was what Freud was looking for when he impoliticly urged his students toward naked self-portraits. What he wanted was for his students to see themselves as more than themselves - to be completely revealed, to put in everything, and, maybe, in the process, to find a certain truth. Determining exactly whose truth is exposed, however, can be a more complicated picture.

Books by Title

Books by Author

Books by Topic