Playing to the Gallery

Helping Contemporary Art in Its Struggle to Be UnderstoodGrayson Perry

(Impt to note that he's called this 'Playing To The gallery' and not 'Sucking Up To An Academic Elite')

Very few people enter the art world to make money. Most do it because they are driven to make art or they love to look at it. That means they are often passionate, curious, sensitive types.

For someone to walk into a contemporary art gallery for the first time and expect to understand it straight away would be like walking into a classical music concert, knowing nothing about classical music, and saying "Oh it's all just noise."

The art world has been fairly inward-looking. The circle of artist, dealer, critic, collector and museum did not necessarily worry about the opinion of the public. Today it is different - the museums are the powerhouses of the art world, and they need to attract visitors to maintain their funding. So the artist who can draw the crowds gets the best seats.

So how do you judge art? How do you decide if it's any good? many of the criteria are problematic and conflicting. We have financial value, popularity, historical significance and "aesthetic" appreciation. And all these things can be at odds with each other.

Beauty is about familiarity. We don't have an innate sense of it; we like what we are conditioned to like by our culture.

The nearest thing we have to an empirical measure is the market. By this reckoning, Cezanne's Card Players is the most beautiful painting in the world as it sold for $260 million.

Yet when a commercial gallery is setting up its show, it usually prices by size - the bigger the painting, the dearer it is.

But then there is 'validation' - being offered at an auction house such as Sotherby's means that the artist has been 'approved'. The key is to understand who is doing the validating. And this involves a large group of characters - dealers, collectors, critics, curators, other artists, and, sometimes, even the public.

(Perry said he once did a pot he called Lonely Consensus. He asked his dealer for a list of the top 50 collectors and wrote the names on his pot "in a decorative way". He won the Turner Prize with it and one of the men named on the pot bought it on sight.)

Critics no longer important - just one of many voices in the art world.

Collectors sometimes people trying to buy respectability to burnish an image of the perhaps dodgy source of their money.

Dealers take a bit of care as to who they sell to. Public museums get a discount because it increases artist's overall value. Other customers are vetted, and may be rejected if they are not prestigious enough (or if they might immediately resell the work at a profit).

Museum curators in a powerful position, and so have a code of ethics which bars them from acquiring art for themselves, or at least in the field in which they are working. Otherwise they might buy a certain artist, then say 'Oh I think we should do a show on X at the museum', and then 'It's funny how X's prices have gone up since we had that show ....'

"For all my jokes, as an artist what I desire is to be taken seriously. I have a horror of becoming trendily fashionable because then there's the inevitability of becoming unfashionable.

International Art English - the BS vocab art writers use to pretend they are serious commentators, but which actually communicates virtually nothing.

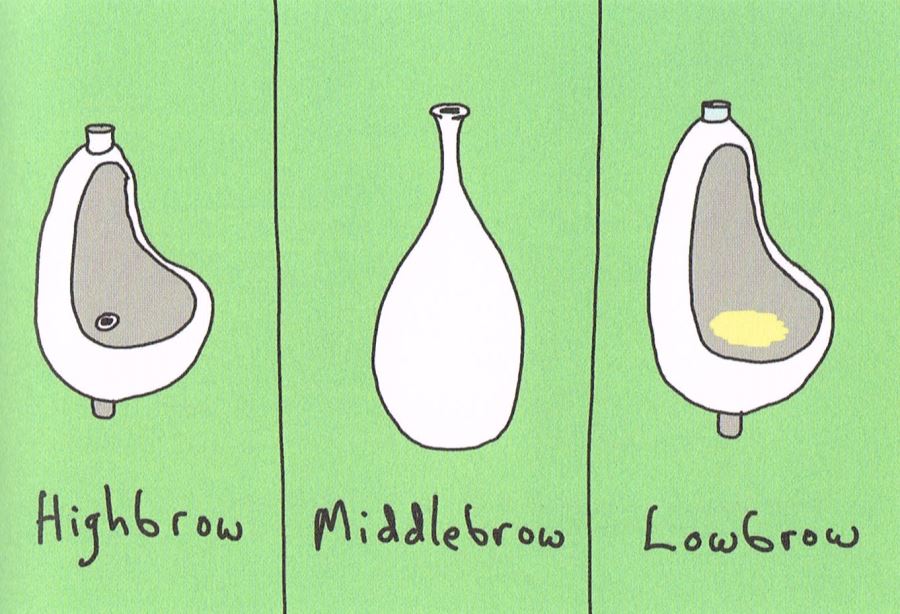

Does something have to be made by the hand of the artist? - Damien Hirst or Takashi Murakami with their hundreds of assistants. The irony of Duchamp's urinal starting as a factory-produced item, but by the time it became collectible, was no longer being made, so Duchamp had to commission hand-made copies.

What is art? Where are the boundaries between 'art' and 'not art'? Some suggest we are in a time of post-historical art, where anything can be art, but not everything is art. There are still boundaries, but they are fuzzier and softer, and continually shifting.

Problem is that there is a lot of "I fancy doing that. Let's call it art." And of course because there's a lot of money to be made - estimated $66 billion in 2013 - there's an incentive for doing so.

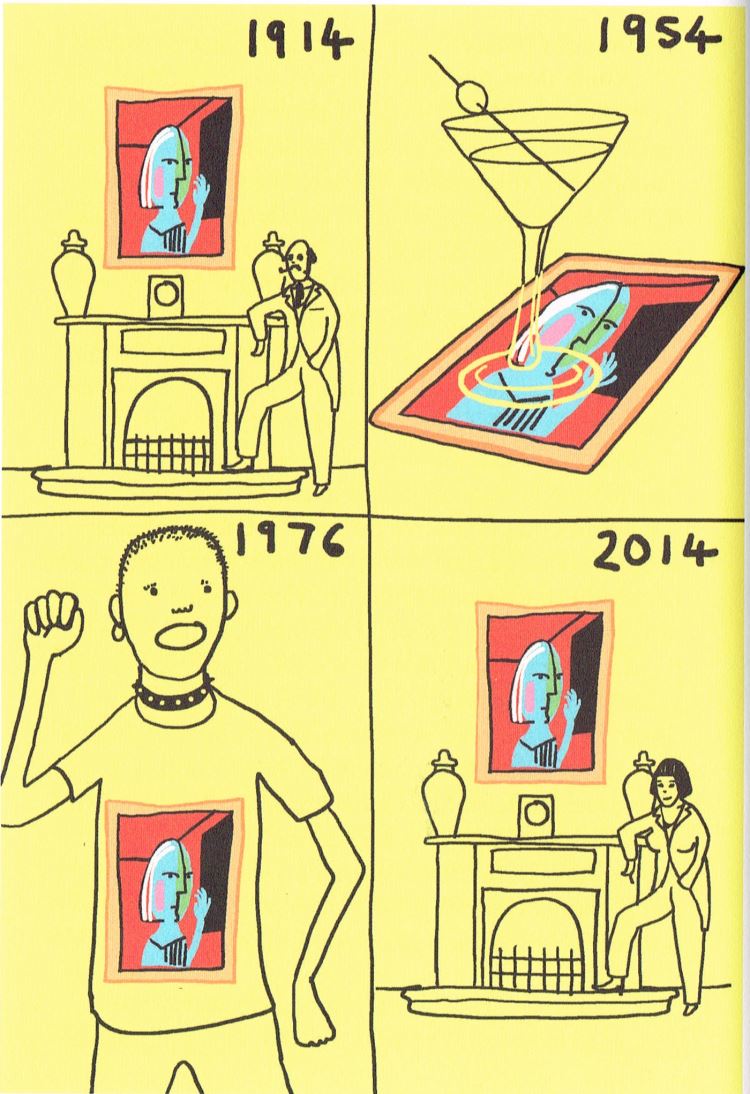

"Art" gas changed through the ages. The Romans had 'high' art - music and rhetoric, and 'low' art - sculpture and painting because they made a mess and were hard labour. The concept of art to decorate your walls, as opposed to tapestries mainly designed to keep out the draughts, dates from maybe 1400. Then, mid C19, people started to question exactly how representative art should be, until, in the 1910's, Duchamp and his urinal.

Duchamp declared it to be art, but many at the time, including most of his fellow artists, disagreed. It took time for the radical new idea to gain acceptance. Banksy painting on a London shop wall of a child worker sewing Union Jacks, was subsequently carefully taken off the wall and sold at auction. Banksy declared that it was no longer a Banksy since it was no longer on the wall. Perry thinks this is a great idea - that the artist can declare his work 'not art' - and wishes he could take it further and declare things he doesn't like as 'NOT Art'.

Group of art students got a grant to put on an art show. The show turned out to be photos of the group frolicking on the beach at Costa del Sol and a few tacky holiday souvenirs. Stirred public outrage at "kids spending public grant money on a holiday and calling it art". But the students turned the tables when revealed that the grant money was still in the bank, the pics were all taken at the local beach, and the souvenirs had come from the local charity shop.

But Perry deplores idea that any amateur mucking about can be classed as 'art' to excuse the mediocrity of it.

Superficial acceptance, but underneath some class snobbery. Some art is more equal than others - a urinal or a shark in a gallery? "Wow that's amazing" - but a pot, now that's craft.

('Beating the Bounds' - an ancient ritual dating back to time before there were accurate maps. Every decade or so, a group of old and young parishioners would walk around the boundaries of the parish, to pass on the knowledge of where they lay. And when they got to an important corner or marker, they would beat the boys with a whip, to ensure they had a strong emotional memory of that exact place.)

So here are some of Perry's bounds that make something "Art".

Is it in a gallery? By bringing it into a gallery, Duchamp transformed his urinal into art. But if you brought a beautiful Ferrari, it would still be a lovely car, but it would be quite a lame bit of art.

Is it made by an artist? In 1995 an artist had a show in which one piece was an actress sleeping in a glass case. Most people agreed that this was art. Then in 2013 the actress decided to do it again, this time at NY MOMA, but without any collaboration from the artist. So was this still art? Traditional bark paintings by Aborigine painters for spiritual and cultural purposes. The painters don't consider themselves artists, they are preserving and continuing their history. So is it art if not made by an artist?

Are photographs art? "We live in an age when photography rains on us like sewage from above." (So he's not keen on it then.) One definition is 'if it is bigger than 2 meters and costs 5 figures or more it's art not a photo'. The highest price of any photo was Andreas Gursky's pic of the Rhine, which sold for $4.5 million. The reason it made that price was that it was the last of an edition of five, and the rest were already in museum collections and so would never be available. So have to avoid the 'endless reproduction' potential before it becomes 'Art'.

The rubbish dump test. Only qualified as Art if it were chucked on a pile of rubbish and someone wondered why a work of art was being thrown away.

Art now quickly goes out of fashion. Media constantly drawn to what they can describe as 'avant-garde' or 'cutting edge'. And of course all artists cherish the idea that they are revolutionary and original. The worst thing you can do is go to an opening and say 'Oh yeah this reminds me of .... ' "Do not do this. This is a bad, bad thing to do."

Problem is that Art is getting quite jaded. It's mostly 'Yeah had that idea already, but that's a great version of it.'

Robert Rauschenberg encapsulated idea of killing off previous art movements by taking a drawing by the reigning modern master Willem de Kooning and carefully erasing it, then exhibiting it as his own work.

Have to keep going further to shock people. Current extreme Chinese artist Zhu Yu photographed eating a stillborn baby.

When, in the early 60's, people encountered Roy Lichtenstein's pic of a leg opening a pedal bin, it was a huge culture shock. Artists found it liberating that this could be Art. But subsequent artists have never had that shock-and-awe.

All the stuff that used to be rebellious - long hair, tatts, drugs, inter-racial sex, fetishes - have gone mainstream (although you still don't see a lot of underarm hair on women). Tracey Emin went really counter-culture and supported the Tories.

(London Times)

WHEN Grayson Perry won the Turner prize in 2003, a journalist asked him, 'Are you a lovable character or are you a serious artist?' and he answered, reasonably: 'Can't I be both?' Which is what he has been ever since, though increasingly taking on another role as a cultural educator, most recently with his Reith Lectures, which form the basis of this jaunty little book.

Perry wants to be helpful, both to young artists and to people who still feel a bit intimidated by art galleries (that is, most people). He wants them to feel 'a little smarter, a little braver and a little fonder' when approaching art. And he carries off a brilliant sleight of hand by saying, reassuringly, that you don't need to know anything at all to enjoy art, while simultaneously smuggling in lots of names, quotes and facts that might come in useful for gallery conversation.

Perry addresses not so much the age-old question of what art is (art, he says, is what you find in art galleries), but the equally tricky question of how you know if it's any good. We know that 'posterity' will reach some consensus down the line, but that's not much use if you're standing in an art gallery today, wondering, is this a load of tosh? And if you are British, you probably are thinking it's a load of tosh because we Brits, far more than any other nationality, are notoriously resistant to contemporary art. But that’s fine, says Perry, because there's a lot of it about and a lot of it is rubbish.

'There's no such thing as good taste' - Grayson Perry guides us around his new exhibition - taste and class.

However, he explains, art usually goes through some filtering process before it turns up in a public gallery. The first and possibly most rigorous judgment comes at art school: if the other students think a work is good, then that is almost the best accolade an artist will ever have. The next stage is when the critics move in. Critics used to be more important than they are now, but in the 1990s their influence was, to some extent, displaced by collectors such as Charles Saatchi, who could enhance the value of a work simply by buying it. Then come the competitions, the prizes, the biennales, which indicate when an artist has definitively 'arrived'.

The general assumption in the art world, Perry says, is that 'democracy has bad taste': if an artwork is popular, then, almost by definition, it must be bad. And, certainly, if you canvassed the public, you'd find Jack Vettriano up in the pantheon. But you'd also find Hockney. Is he bad? Just because people like him? Perry thinks not - though he has a sour word for LS Lowry, whom he finds 'repetitive'. But 'if quality smacks of elitism, what form of art should the proles have'? What indeed? Perry never really finds the answer. But whereas in the past the art world could be an entirely inward-facing transaction between artists, collectors and 'cognoscenti', nowadays it is far more complicated because it needs the public, too. Collectors like to buy artists who are shown in museums, and museums, if they are in receipt of taxpayers' money, also need attendance figures.

Perry says he gets fed up with being the poster boy for handmade art - and nowadays, he draws his tapestries on Photoshop and has them woven by computer-controlled looms - but he is still closer to the old art/craft tradition than most contemporary artists. He tends to disdain video and photography, and sniffs: 'We live in an age when photography rains on us like sewage from above.' He recalls that he once asked the brilliant photographer Martin Parr how you distinguished an art photo from an ordinary one and Parr told him you could tell it was art if it was 'bigger than two metres and priced higher than five figures'. This book is full of good jokes like that, full of cartoons, full of memorable epigrams, but above all full of thought-provoking ideas that make you want to pause on every page and say: 'Discuss.' I have never read such a stimulating short guide to art. It should be issued as a set text in every school.

More books on Art

Books by Title

Books by Author

Books by Topic